Among the many things that can make the heart pound—a new love, a scary movie, a vigorous workout—an irregular heartbeat known as ventricular tachycardia is particularly dangerous.

Errant electrical signals make the heart race, sometimes too fast to pump blood. Patients may faint, and prolonged arrhythmias can even cause death. All too often, ablation procedures that aim to scar small sections of heart tissue contributing to the arrhythmia simply fail to work.

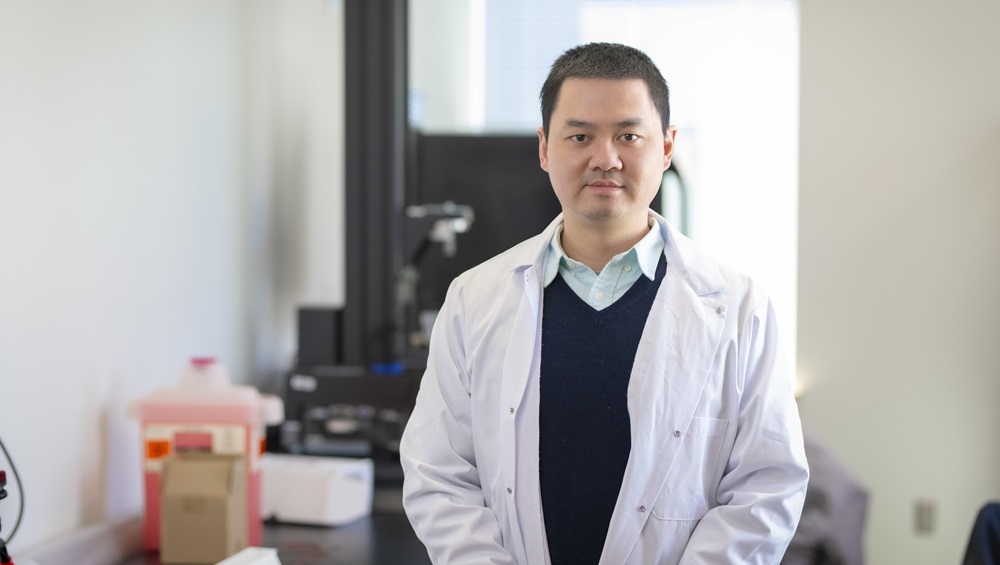

WPI researcher Shijie Zhou is working to change that by using large sets of data from noninvasive clinical tests, computational methods, and artificial intelligence (AI) to reconstruct cardiac events such as arrhythmias in digital models. His goal is to make ablation procedures safer and more accurate. With funding from the American Heart Association (AHA) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Zhou is developing technologies that can precisely map electrical circuits in the heart, pinpoint problem spots, and identify the best sites for treatment.

“It is very challenging to treat ventricular tachycardia,” says Zhou, an assistant professor in the Department of Biomedical Engineering. “After ablation, ventricular tachycardia recurs about 30% to 70% of the time. However, with algorithms and data gathered from many patients, we can build tools that will enable clinicians to work toward better outcomes for patients.”

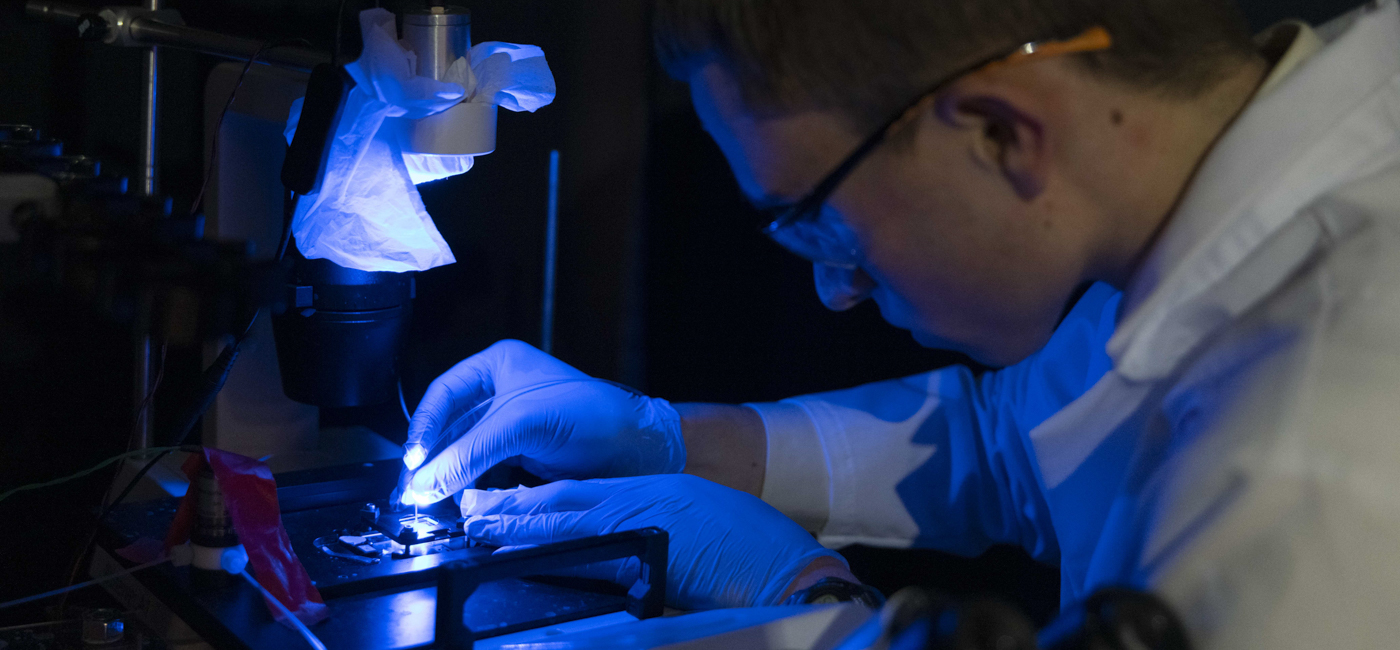

Ventricular tachycardia originates in the lower chambers, or ventricles, of the heart and is often caused by heart disease. Treatments include drugs such as beta-blockers, implanted pacemakers, catheter ablation, and radiation. A minimally invasive procedure, catheter ablation involves inserting a long flexible tube into a blood vessel, guiding a probe to a specific spot in the heart, and then using radiofrequency energy or extreme cold to scar the tissue and block irregular signals.