When you think about the critical issues facing humanity, pond scum might not come to mind. But for the City of Worcester, pond scum is an ongoing problem that recently presented WPI students with an opportunity to develop hands-on scientific research skills while simultaneously giving back to their community.

Three first-year students in last fall’s Smart and Sustainable Cities section of the Great Problems Seminar (GPS) developed recommendations for a water management system for Crystal Pond, which lies at the center of Worcester’s University Park, near Clark University.

In the height of summer, much of the water in Crystal Pond is covered by thick clumps of filamentous algae—the more scientific term for pond scum. The algae provide food for insects and other invertebrates that live in the water but they also are a problem: The unsightly brown and green globs block sunlight from reaching plants that live below the surface, and they can steal oxygen from fish.

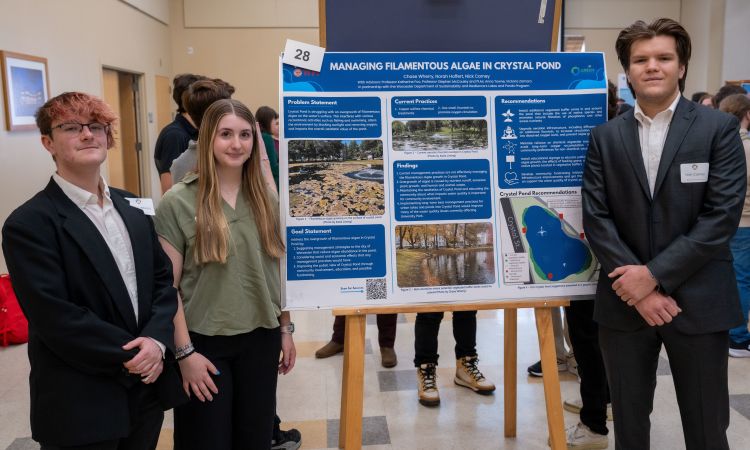

After getting an overview of the issues at Crystal Pond from Katie Liming, the lakes and ponds coordinator for the City of Worcester, teammates Norah Hoffert ’29, Chase Wherry ’29, and Nick Carney ’29 researched how other cities and towns have managed filamentous algae growth.

“By focusing on one pond, we could go more in-depth and make more specific recommendations, which ultimately could make a bigger impact,” says Hoffert, an architectural engineering major, noting that the team’s recommendations could be adapted to meet the needs of other ponds and lakes throughout Worcester.

Cultivating collaboration

The partnership between the GPS class and the city was mutually beneficial. The two-term course is designed to introduce first-year students to WPI’s signature project-based curriculum while learning how to do university-level research. This year marked the first time that each of the student teams in the Smart and Sustainable Cities section worked directly with a representative from the cities of Worcester or Cambridge on a topic related to existing municipal projects or goals.

From left: Chase Wherry, Norah Hoffert, and Nick Carney during the GPS poster presentation

The idea to have teams conduct research for specific municipal projects grew out of work that Stephen McCauley, who co-teaches the section, does with the Green Worcester Advisory Committee, a volunteer group of city residents that supports the Department of Sustainability and Resilience. He approached city officials about partnering with student groups and they responded enthusiastically.

“They took my initial list of project ideas and revised it to focus on specific projects that would be really helpful for the city,” says McCauley, associate professor of teaching in the Department of Integrative and Global Studies (DIGS).

He collaborated with co-instructor Katherine Foo, assistant professor of teaching in DIGS, to ensure a reasonable scope for each project, given WPI’s accelerated term schedule. The pair then worked with the 27 students in the class to develop seven teams.

All of the Worcester projects related in some way to environmental conservation or sustainability. In addition to mitigation options for the algae at Crystal Pond, teams examined the effects of PFAS, or “forever chemicals,” in artificial turf fields; the benefits of large canopy trees; managing invasive species; adjusting ordinances to allow for landscaping with native plants; and evaluating infrastructure challenges related to green design guidelines. A final team explored options for expanding the City of Cambridge’s participatory budget process, which allows city residents to choose specific projects to get some public funds.

Mekhi Howell explains his team’s research about green design guidelines, which was one of the winning projects at the GPS poster presentation in December.

Teams unveiled their recommendations in early December to WPI faculty, students, staff, and alumni who attended the GPS poster presentation, the annual event showcasing work from students in all of the seminar sections. This year 41 teams from eight sections participated.

In a separate session, students in the Smart and Sustainable Cities section offered their recommendations to their municipal project sponsors, who had a chance to ask questions.

Long-term benefits

The Crystal Pond team settled on a three-pronged, long-term approach to minimize runoff from nutrients responsible for the algae:

- Add more vegetative buffer around the pond, prioritizing native plants.

- Upgrade the pond’s existing aeration system.

- Place educational signage throughout the park to discourage people from feeding the geese.

“It’s not necessarily the geese themselves that are the problem,” Hoffert explains. “It’s the goose poop, which gets in the water and causes excess nutrients.”

All three team members enjoy knowing that their work could result in a prettier park for members of the public to enjoy. And even though what they learned about water quality during this project isn’t directly applicable to their chosen fields of study, they know they learned valuable skills.

Wherry, a biology and biotechnology major says, “Coming up with ways to implement viable options will definitely be useful in the future—no matter what major you’re going into.”