Follow The WPI Podcast on your favorite audio platform

E13: Wildfire Research, Part One | James Urban, assistant professor, and Albert Simeoni, professor and department head, Fire Protection Engineering

Researchers across departments at WPI are studying how wildfires start, spread, and impact communities. In this episode of The WPI Podcast, James Urban, assistant professor in the Department of Fire Protection Engineering, and Albert Simeoni, professor and head of the Department of Fire Protection Engineering, discuss their research on fire behavior and how they’re working to share the knowledge generated from this research to protect people and property.

This is the first of two episodes focused on wildfire-related research at WPI. In the next episode on the topic, researchers in the Department of Civil, Environmental, and Architectural Engineering will talk about their work to understand the impacts of wildfire smoke on indoor environments, with a focus on children’s sleep health and the absorption of smoke by building materials.

Related links:

Wildfire Interdisciplinary Research Center

National Fire Protection Association: Firewise USA (wildfire risk reduction program)

Transcript

Jon Cain:

Chances are you’ve seen news coverage about devastating wildfires.

Wildfires burned nearly 9 million acres and destroyed more than 45-hundred buildings in the U.S. in 2024.

Then in January 2025, wildfires in the Los Angeles area burned more than 40-thousand acres and killed 30 people.

The lives lost, families uprooted, and the properties damaged are some of the reasons why researchers at Worcester Polytechnic Institute study wildfires.

They’re working to understand how fires start, how they spread, and how they affect air quality *inside* homes and businesses.

The goal is to help communities and homeowners better prepare, to *advise policymakers* who make decisions on building codes, *guide property managers* to design healthier buildings, and *help parents* set up bedrooms to minimize their children’s exposure to wildfire smoke particles.

Hi. I’m Jon Cain from the marketing communications division at WPI. This is The WPI Podcast. We bring you news and expertise from our classrooms and labs. I’m here at the WPI Global Lab in the Innovation Studio on campus. This is the first of two episodes exploring wildfire research at WPI. We’ll begin with the work being done in our Fire Protection Engineering Department. And in an upcoming episode, we’ll explore research on wildfire smoke from our Civil, Environmental & Architectural Engineering Department. Over the two episodes, we’ll talk with four people at WPI who can help us better understand wildfires and their impacts…

We’ll start this episode with a researcher whose lab looks at many aspects of wildfires. James Urban is an assistant professor in the Fire Protection Engineering Department at WPI. James, thanks for joining the WPI podcast.

James Urban: Thanks for having me.

Cain: Throughout this series of interviews, we’re going to talk a lot about wildfires, their impact and how people can protect themselves. So, let’s start at the source, the fires themselves. James, you do a lot of research on how fires start and spread. What are some of the research projects you’re working on?

Urban: So, we have several projects going on that are looking at these aspects of wildfires. We have one project that’s funded by the state fire agency in California or Cal Fire looking at how nearby objects such as ornamental vegetation around houses can affect how fire can spread to those homes. As well as, uh, looking at how some of the fires how they’re started by utilities when, um, power lines can clash in high winds that can eject metal particles, which can land on the ground and ignite fuels. And then, in these wildfires, one of the main ways in which structures are ignited is these things called firebrands, which are burning pieces of wood that get blown by the wind. We have various projects looking at how they’re generated and then how they ignite receptive fuels such as wildland fuels or structural fuels.

Cain: Yeah, a lot of different aspects there. When you mentioned firebrand, would some people call those embers?

Urban: Yeah, the main difference between an ember and a firebrand is the firebrand is in motion. It’s, uh, flying through the air. But yes, it’s the same embers you might see in a campfire. Just they’ve been blown by the wind and carried downwind where they can then start a new fire.

Cain: Great. We’re gonna delve into, um, a lot of those different research areas that you mentioned. One area you’re looking at is wildland urban interface fires. Uh, can you tell us what those are and why they’re becoming a growing concern in your view?

Urban: Sure. So a wildland urban interface fire or often when we call it a WUI fire, you know, nothing to do with the city of Worcester or anything like that. Um, but it’s this wildfire where it’s actually begun to move into the built environment so, you know, you can think of an urban area where you have maybe a neighborhood, a subdivision, or a small town. And realistically when you hear, you know, see on the news something about, you know, homes being destroyed in a wildfire. It is a WUI fire or these wildland urban interface fires. They’ve definitely become more common. There’s a lot of different factors at play. There’s, you know, things like climate change, but also people are building, more and more into, wildland areas and exposing themselves to this, the sort of the, the threat from wildland fires, but also the people themselves are typically the ignition sources for these fires. And so then you’re increasing the chances of an ignition. And then also people that are at the places where they’d be vulnerable to them. So that’s why we’re seeing more of them lately.

Cain: Gotcha. Can you talk about some of those human driven ignition sources? Um, is it campfires or, um, lawnmowers? Uh, what are some of the items that might cause something like that?

Urban: So it can be almost anything. And I think I just to maybe flip it around for a second. Let’s think about how a fire could be started from nature. And realistically, there aren’t very many options. You’ve got things like lightning, which I think is the most common. You can have things like spontaneous ignition, which can happen, but usually not very likely to happen in a natural scenario. Or you can have maybe have something like, you know, lava from a volcanic eruption or maybe a meteorite, but really, like we’re talking about sort of, chance events there. But when you’ve got, people around, there’s all sorts of things. I mentioned utilities. Um, so when you have power lines, clashing, they can either. Directly heat a tree electrically, um, and ignite it that way. Or they can shoot hot metal particles on things that ignite them. You can also have, uh, you know, people could be driving down the highway and have chains dragging, behind their car or if they get into a car accident. All these activities can create sparks, which can then, ignite, uh, fuels in the side of the road. People can discard a cigarette butt. You can be not very careful with your campfire. I mean, I guess I could keep going on and on and on. But it’s essentially anything that generates heat is something that could cause these fires.

Cain: Yeah, I think it’s a good reminder. ’cause you know, you might think, oh, well it’s just something that happens in the forest and it’s not gonna affect me. But you’ve laid out some examples of just how quickly something can happen and, and uh, it’s interesting that wildland urban interface, more people moving into those types of areas, they’re pristine. You know, they, they want to have the nice view or whatever. So, I think I was reading some statistics that there’s a pretty large percentage of the country that is sort of susceptible to this type of fire.

Urban: Oh, for sure. Um, and I think especially it’s, uh, it’s interesting because there’s two sides of it. There’s a lot of expansion into these areas, but there are also places where. We have, um, a lot of, communities in what we would call the wildland urban interface. And, you know, some of these places traditionally maybe haven’t had that much of a fire hazard. But you know, as, uh, things like climate change go on, that may change.

Cain: You mentioned that you’re looking at a lot of different factors of wildfires in particular, um, how they spread, uh, we talked about firebrands. I think a lot of people might assume that wildfires sort of spread in this, you know, point A to point B, this predictable manner that, you know, you have a flame and it comes into contact with, uh, an object, whether it be a tree or the next building over, and then that flame touches the next one and it, and it goes on and on. But what you’ve found in your research is it’s not that direct, right?

Urban: I’d say in some ways it makes sense in the way that, you know, fire has to move from one thing to the next. But I think, a lot of times when people, maybe even myself included, you know, or less so now, I guess, I had this impression of fire being, you know, a wall of flames that maybe would move through a community. But instead what we see is it’s more of a leapfrogging between, fuels that are maybe separated by, say, short-cut grass or roads. And, um, so there’s sort of this discontinuous aspect of it. And I think that’s where we’re seeing how the fire is spreading. And that’s a very difficult thing to model the behavior of in comparison to a fire spreading through say a field of dry grass.

Cain: Gotcha. What has your research shown about, uh, the role of firebrands and the role of wind in spreading, uh, flames during wildfires?

Urban: Sure. So, um, in general, I would say wind is one of the most important factors for any sort of wildfire spread, but especially firebrands. With firebrands, it affects, um, how the firebrands are broken off from the burning. You can imagine like a burning tree or a burning house. As it’s burning, it’s becoming more fragile. And then the aerodynamic loading from the wind is what’s actually breaking off the individual embers that then can be transported by the wind. And so that’s also how they reach farther is the wind. And the wind is also playing a crucial role by allowing those firebrands to burn and, um, maintain a, a temperature that may be capable of ignition when they land on something and ignite it. And so, you know, sort of at every stage the wind plays a critical role. And even when they’re deposited, we found, like on a fuel, what we found is the wind has the strongest impact on their ignition capability compared to all the parameters we studied.

Cain: Is that why we’ve seen some of the larger wildfires in the US recently, uh, Maui and L.A. Those were situations where there was really, um, extreme, uh, levels of wind associated uh, with the, situation.

Urban: Oh yes. So, the wind, we were just talking about the firebrands, but it also, when you’ve got a flame, it allows it to blow. It sort of pushes the flame over and so it can come into better contact with the unburned fuel and that can heat it up faster and then allow it to spread faster. So, um, wind plays a very major role in, um, why we’re seeing these, uh, much more severe fire events.

Cain: So we’ve talked a little bit about how, uh, fire spreads and how flames travel. Um, and it kind of gets me to one other area of your research, um, something called defensible space. I’m wondering if you could define what that concept is and then we’ll talk a little bit more about the research.

Urban: So, in general, uh, defensible space is this idea that you can have, you know, a structure or any sort of item that you might care about, and that there are items around it which are flammable. And if they aren’t, protected or if they’re close enough to the thing you’re trying to protect, they could act as a pathway for the fire to reach the thing that you’re trying to protect or like in this case, you know, somebody’s home. And so for example having very tall trees that are flammable nearby your home is a very dangerous scenario because if they get ignited, then they will almost certainly ignite your home. Whereas if they were set back by a certain critical distance, then that will prevent the fire from spreading from one to the other. And now that critical distance depends on the flame characteristics, but also fire brands. Um, and some of our research is trying to figure out how do we use computational fire modeling tools to predict what that distance should be. Because right now there isn’t really a lot of, scientific research or scientific understanding, telling us what that distance should be. There’s, just some sort of loose guidelines that have worked pretty well so far, but we don’t really know when exactly they work and when they don’t.

Cain: Does the research also look into the type of material that’s around the home? Obviously not all materials are created equally. You’ve talked about trying to figure out that right distance, uh, you know that something can be away from a house. Does it also make a difference what type of material it is that may change the equation a little bit?

Urban: Oh, definitely. Um, and so that’s sort of another aspect of, um, structure defense in WUI fires is what we call home hardening. And so it’s using, um, materials or in construction methods that are more resistant to, uh, these, um, pathways for fire propagation into structures.

Cain: You mentioned some of the partners in your research. Uh, tell me a little bit more about who you’re working with on this research.

Urban: Our research is funded by a combination of federal agencies, state agencies, and, private companies. We have several grants that are funded by the National Science Foundation including one that is to establish a wildfire center in particular, it’s what’s called an N-S-F IUCRC or an Industry University Cooperative Research Center. And so that one is called, uh, WIRC, or Wildfire, interdisciplinary Research Center. And for that we work with, industries and some state and federal agencies that are impacted by wildfires. And we develop research that is, um, more, close to application and, you know, use on the ground for actually being, used in a year or so. In comparison to a typical NSF grant. We also have some funding from the Department of Defense, which does a lot of what’s called prescribed burning, which is to reduce the fuel load of the wildland areas. And that’s looking at wildfire smoke. And then, um, we also have a project through the U.S. Forest Service, looking at firebrand generation.

Cain: You know, you’ve mentioned a lot of different aspects of wildfires that you’re researching. I’m wondering how you do it. ’cause when I first heard about this, I thought, okay, they must be going out in the field on site. But we actually, at WPI have a lot of labs where you’re doing this. Uh, tell us how you do this, uh, breadth of research and, and you’re able to do it here on campus.

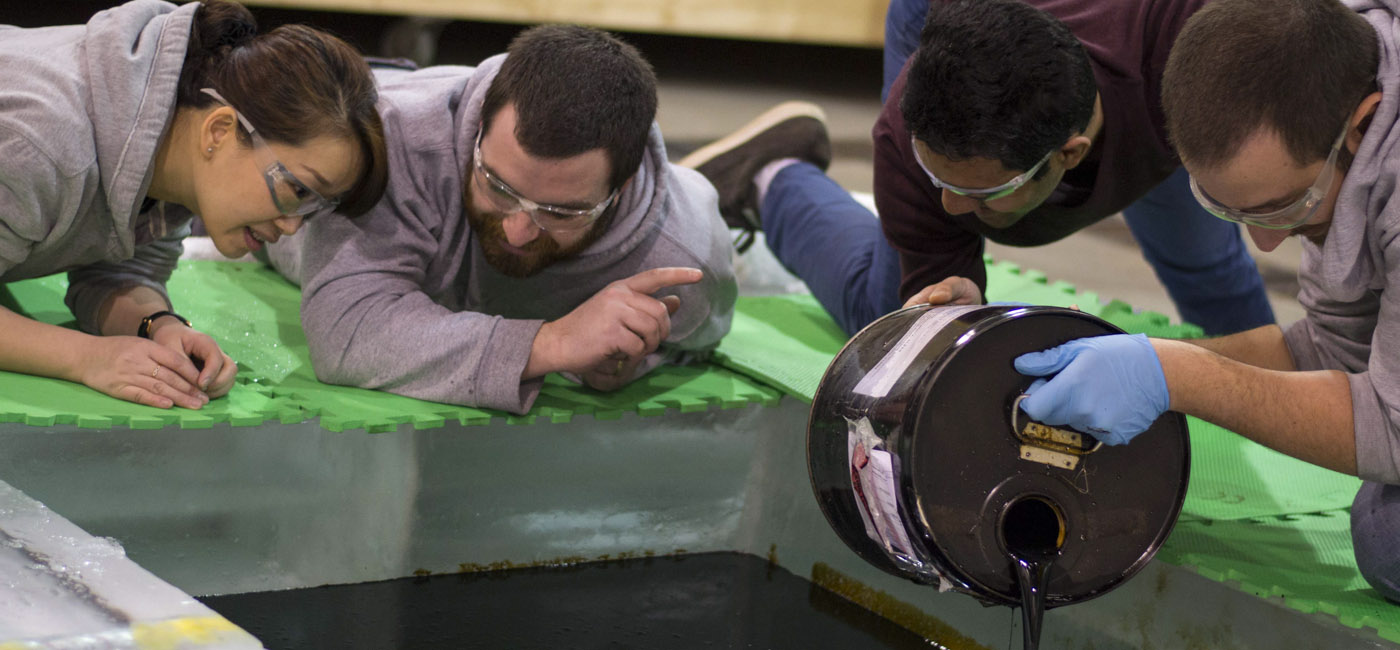

Urban: Sure. So for some of it we have to make very specific, small scale experimental apparatuses that we can sort of take the wildfire problem, identify a key aspect of it, and sort of shrink it down to its basic components and do controlled experiments in the lab. And so those are things, uh, where you may have a fire that in theory you could kind of hold it in your hands, you know, maybe you’d need some very thick gloves ’cause it’d be hot. But, um, it’s not very big. But we also have a very unique testing capability in, uh, the Fire Protection Engineering department where we can burn, um, very large, um, objects. So, in particular, we’ve burned as many as, uh, four trees at the same time. Um, and we can, uh, do these large scale tests in the lab, including using a wind tunnel to sort of do bigger scale experiments, um, of what you might see in a wildfire, but still not maybe the full scale that you could actually do in the field. Um, and there are some folks that also do field experiments. Um, but most of what I do is, is grounded in the lab.

Cain: How do students get involved in this research, whether it be, grad students or undergrads and your PhD students?

Urban: I supervise some MQPs and so, um, one that sticks out to me where there was a group of students that came to me and also. Professor Pinciroli in the, robotics department where they wanted to make a wildland firefighting robot. And one of the students had grown up in the Bay Area and seen, uh, these fire goats. They have these, goats that are, you know, owned by somebody and they bring them around to different green areas and they eat the grass. And that’s a way to reduce the fuel for a potential, wildfire risk. And unlike things like a lawnmower, there’s no chance of them sparking a fire. And so in my own time, you know, that I spent in California in grad school, I remember seeing the goats up on the hill, trimming the grass. And so, um, you know, for this student, that was sort of a, a triggering moment, I guess, for them with their MQP and they, developed this idea of, you know, can they make something maybe a little bit more mechanical than a goat? And I guess a GOAT is a good, inspiration for a WPI student. Um, but they ended up making a small, little scaled down robot that would be able to dig a fire line like, wildland firefighters do. Um, and so that was, I guess, an example of somebody who was inspired to get into this from their own experience in living in an area that has some sort of an elevated fire danger. I think a lot of students are drawn to it because it’s a very complex problem. Uh, there’s topics that you can, um pursue in graduate school such as like heat transfer, fluid mechanics and then also combustion. And our research is a combination of all three. And so you have this really kind of, uh, vicious and pernicious, uh, multiphysics problem. And so it’s, uh, there’s always more you can do. There’s always, uh, the richness that you can’t deplete. And so I think a lot of students like that.

Cain: Yeah. And this is a topic that students can come to WPI to get a degree in. and to carry that, education forward once they’ve graduated. Uh, you mentioned the MQP, that’s the Major Qualifying Project, which is a senior, level project here at WPI. You are doing so much research on this topic, how do you hope that the public will benefit from, what you and your students are doing in the lab to research this problem?

Urban: I think one way in which we could see, you know, the research we’re conducting, having some real world impact is, uh, if we go back to that research I was talking about related to defensible space, part of our goal is to enable, fire protection engineers or other engineers to be able to perform, basically fire hazard analysis for a given property. And so when they’re designing the property, they can actually consider what sort of wildfire threats the home will face and how things like landscape, around the home, different types of ornamental vegetation, trees, bushes, et cetera, will affect the wildfire exposure to the home. And I think right now we don’t have a good way for that to be done with a scientifically rigorous approach. And if we can do this that’ll allow people to do that analysis. And I think if you look at the threat from indoor fires, we already have analogous tools and approaches. And so I think really we’re missing this, uh. Fire threat from the outside and we’re hoping to provide that.

Cain: You mentioned earlier, one of the possible, ignition sources for fires can involve utility lines or other sort of sparks that occur. Um, tell me about your research in that area.

Urban: Sure. In high winds, in high heat. Um, it’s actually kind of interesting, the elevated temperatures will cause the utility lines to expand a little bit. And so then they’ll sag a little bit more than they normally would. And then the wind causes them to swing back and forth. And eventually, if everything goes wrong, they can come into contact with each other. And, uh, this is called conductor clashing or line slap. That can cause an arcing event and that can generate hot metal particles, which then can be, blown by the wind and then brought to flammable material in the ground such as dry grass and ignite it. And there’s other ways too, in which power lines can potentially ignite fires. But a really dangerous thing about this is, as I was sort of setting this up, we have high temperatures and then also high winds. And so that tends to lead to an elevated fire danger. And so I think there were some researchers outside of Australia. They’ve also had the same sort of issue with their, um, with power line induced fires that these fires tend to be maybe not the most common source of fires that are generated. But when there are big fires, they’re overrepresented. And that’s because they, they typically only happen in elevated fire dangers. And so a lot of the really big fires that we see tend to be these fires. And so it’s an important area to study.

Cain: And what types of, um, things are you studying in that area? Is it sort of better understanding what causes that or trying to figure out factors that utilities need to be aware of to know, like when they need to turn off the power lines or something like that?

Urban: Yeah, so I think there’s definitely an element of the research is to enable the utilities to be able to better make more informed decisions about how to, mitigate, the risk of this. And so you mentioned turning off the power, and so the, there’s a common approach, or more recently a common approach is what they’re called public safety power shutoffs, where they will turn off, part of the grid for usually a short period of time when there’s an elevated fire risk. Another thing that’s been done is to, bury power lines, which is, very expensive, but you put them underground and then, they can’t really be blown around by the wind. And then there’s other aspects of reconfiguring the grid and maybe even creating sort of less centralized or less connected grids so that, communities can be, more resilient to these power, safety, shutoffs and also less transmission lines through these minimally inhabited areas. But in general, the utility companies have a lot of uh, ground to cover. They need better tools to understand the risk. And so by doing research, investigating, how these metal particles ignite fuels, we can then use those with models to predict what would be the fire hazard of a certain type of vegetation nearby a pole and do they have to cut, 10 feet away or 20 feet away, et cetera.

Cain: Gotcha. It’s really, really important work. James, thanks so much for talking with me about your research.

Urban: Thank you for having me. It was my pleasure.

Cain: James Urban is an assistant professor of Fire Protection Engineering at WPI. Next up, we’re staying in the Fire Protection Engineering Department. We’ll talk now about some additional research underway and what WPI does to take research and bring the knowledge learned from it out into the world to create change. I’m joined now by Albert Simeoni. He’s a professor and head of the Fire Protection Engineering Department at WPI. Thanks for being on the podcast.

Albert Simeoni: Thank you.

Cain: So, Albert, you’re a former firefighter. You’ve been on the front lines of battling wildfires. What motivates you to research wildfire behavior?

Simeoni: It’s, um, long personal motivation to do something in this area. I was a student and a researcher before I started to be a firefighter. So it’s kind of, um, uh, wanting to have a better sense of what wildfires are brought me to firefighting, because I was doing that in my education and my research. I grew up in the place of France that burned the most. So, that helped me to, select my, PhD topic. And I was offered several options. And one was wildfires and I just took that one.

Cain: When you were a firefighter, how many years, uh, uh, were you doing that job?

Simeoni: So above 10 years, maybe like close to 12. And, I did everything, you know, from EMT to road rescue, to, firefighting, urban firefighting, then to wildfire fighting.

Cain: So here at WPI, I am wondering if you can tell me a little bit about some of your ongoing research that relates to wildfires.

Simeoni: So, our research is linked to fire protection engineering. What do you do in fire protection engineering? You do engineering, design and, uh, engineering studies to protect people, property and the environment. And, so we’re doing the same in wildfires. A lot of our research it’s linked to fire science, which is for us, a lot of heat transfer, fluid mechanics and combustion. So we’re really looking at the drivers of fire behavior or fire spread and fire impact. It is in the general context of protecting people. So it can cover also evacuations, safety of first responders, uh, beyond our core, which is the modeling of fire spread, the modeling of fire impacts and how you can develop solutions to make communities more resilient to wildfires.

Cain: So when I think about wildfires, obviously I think about the great wide open. Um, you know, I’m wondering where you do this research, is this something that you can do in the lab or does it involve field work as well?

Simeoni: So, we’re doing research in the field, and that’s an important component of what we do. We don’t go to actual wildfires, but we do experimental fires. We go on prescribed burns by our partners who are doing fire management also. But, you know, we like very much the lab because you can control well conditions and systematically study some, aspects of, uh, fire behavior and fire impact. So, one of the big challenges in wildfires is that it’s, happening at a very big scale. You know it’s even bigger than an urban, like a fire, a house, or plant burning. It’s even bigger than that but at the same time, the combustion is very small. It’s below like a quarter inch or something. And so, we have to span these different scales because different things happen at different scales. The role of pyro cumulus, which is a cloud created by a wildfire, there’s no way you can reproduce that in the lab. But in the meantime, uh, the effect of wind to activate the combustion of vegetation, you can reproduce in the lab and do, measurements. So, one of our big challenges is to span all these scales.

Cain: I’m wondering if you could tell me a little bit about how WPI students are involved in this type of research.

Simeoni: So our students are involved at different levels. I mean, they’re across the, all the scales. So let me take an example. We are doing, a field experiment with the US Forest Service and the University of Georgia at Savannah River National Labs in South Carolina, because the University of Georgia has a plantation there and a research like forest. And so, I have a PhD student who’s there with one of our research professors and they’re doing burns in the forest. So, uh, we’re doing quite a bit of that. Of course it’s very demanding, you know, in terms of, uh, time, resources and energy. But we also then get back to our lab and, you know, that we have one of the biggest labs, uh, in the country and the biggest one in academia. So we can burn things like, um, a tree or a couple of trees. We have a wind tunnel where we can do fire spread over vegetation beds, like pine needles or small shrubs. And then we have a smaller instrumentation when we can burn something that would be four inches by four inches. And, uh, uh, when we do that, we’re really looking at more detailed, internal like, combustion processes in the fuel and how they ignite. So we’re trying to cover all the scales and our students have opportunities to, work in the lab, of course, collaborate with other, uh, faculty, but also go into the field and work with the fire managers, and the end users, which is pretty exciting.

Cain: Yeah, you mentioned some of the collaborations that expand outside of the university and, you know, I understand that there’s really, international efforts, that WPI Fire Protection Engineering is involved in.

Simeoni: Yeah, so it’s a national, for instance, we have a NSF, research center with, San Jose State University in California and we want to burn a whole canyon in California, with them. So that was great. And our students could be in contact with other students and our faculty too, you know. And this center also involved, um, members of the industry, like utility companies, insurance companies, technology companies, which is a very good exposure for our students. So, the canyon, it’s an interesting one because in canyons you can have some, what is called a fire eruption in Europe and in other places, and fire blowups in the US it’s basically when your fire enters the canyon because of the close configuration of a canyon, uh, it’s gonna have some feedback that will make it accelerate. And we had, all over the world accidents for firefighters. It’s also, even if firefighters are not caught in these, uh, blowups, it’s challenging to fight. It also has consequences about how you build close to the canyon and, what you have to, basically design for inn terms of, fire resistance. And so, we, with, the support of Cal Fire, which is the firefighting agency in California, we, burned a canyon. So they did, they burned everything around so it was safe before, like the week before. And then we burned the whole canyon and we let the fire go and, uh, uh, some, uh. utility companies and their, some technology companies that are providing a service to utilities, put poles and protection for these power poles because also, you know, burning the infrastructure is a big problem in wildfires. And, they looked at the maximum impact when the power line is on the ridge, on top of the canyon. And we were able to measure fire behavior and the team at San Jose State, their atmospheric scientists, and so we call them fire weather specialists, and they measured the interaction with the, uh, atmosphere and also the wind which was created by the fire around the fire. So that was a very interesting experiment at a very large scale. The canyon was two miles long, and that was a very exciting project and we sent three people from WPI there to help with this project. And then we have research projects with the European teams, from. France, Portugal, Spain, also, Australia, and, um, South America. This problem is global. So, we’re really trying to cover the different aspects and, uh, uh, use the leverage between, uh, the knowledge that other teams have, their capabilities, but also their problems. So for instance, Australia, uh, it’s, uh the driest continent on earth. And uh, also it’s very impacted by climate change. So they’re experiencing large wildfires and extreme conditions that we think we’re gonna experience in the US in 10 or to 20 years.

Cain: Wow. It’s definitely sounds like there’s a lot of stakeholders that are interested in this information. I’m wondering if, you can talk a little bit about sort of direct engagement with, firefighters themselves. I understand, uh, you had the opportunity, to work with some firefighters in Greece.

Simeoni: Yes. So with firefighters, as I told you before, it’s a global problem. So we’re really trying to, bring solutions for the global community. You know, uh, in university you have universal, right? So we’re not only looking at our backyard and even our country, but we’re looking at how can we help with this problem globally, you know? And, uh, so, we of course, have a very good relationship with the end users in the Northeast. In the US, we’re working, with CalFire on the West coast. But at some point even with all the means we have in the US, we cannot, really, prevent those disasters. There are wildland urban interface fires. So there are fires like the LA fires, you know, closer to us, there was a fire in 2016, if I remember well, in Gatlinburg in Tennessee that destroyed the town of Gatlinburg and killed people. And, so these wildland urban interface fires or WUI fires like we call them, we can share this experience with other countries and, and, uh, provide training. And that’s what we did with the firefighters in Greece. So we went there for a week. We used, experts from the US and from Europe, including from Greece. And we did a, a course on, fire behavior and WUI fires for over 30, almost 40 firefighter officers from Greece. So you had people, they have military grades in Greece, from lieutenants to lieutenant colonels getting the training and they were very interested. It was a very interesting experience. In the US, we’re helping the fire managers and we really, through our research, we’re trying to help them to make the right decisions when they put fire on the ground for management for prescribed burns. And, uh, so a lot is about, of course, the fire management and not having the fires escape, but a lot is about the smoke, something which is very, relevant to Massachusetts and New England because we saw that in last October when we had smoke everywhere. When you’re doing fire management, you don’t want the management to be worse than the wildfire and send smoke towards schools, nursery homes, and populations at risk.

Cain: Yeah, there’s a lot to think about with prescribed burns that that’s important to, to do them. But it’s also very interesting that you talk about understanding how to do them properly so it doesn’t impact the, community in a negative way. Sounds like there’s a lot of different ways that you’re taking this knowledge and bringing it out into the real world. Um, I imagine there’s a workforce development piece as well to, the research and study that’s happening here at WPI. Yes, absolutely.

Simeoni: You know, prescribe burns. It’s something very well established in the United States, and there is training and uh, uh, usually people do that, have a fire management/forestry background, you know, but I think there is a big, gap in the development of engineering solutions to make our community safer. So for that one, it’s particularly. Something we’ve done for fires already. You know, you’re getting into houses and there are smoke detectors. You know, you’re getting into buildings and there are evacuation routes. There are sprinklers in some buildings and so on. So, for wildfires, we see these massing fires that start as a wildfire and then become a fire through a community. It can be suburban or even we’ve seen for the Eton fire, for instance, one of the LA fires, through, an urban area, and so here, there is a design that we did as a fire protection engineering community to make our cities faster when they were burning a lot. Uh, at the end of the 19th, uh, century, beginning of the 20th century, I’m thinking about the Great Chicago fire, the great Baltimore fire. We don’t see that anymore, but now we see wildfires destroying urban areas and uh, so that’s very well in line with fire protection engineering. And so we need to develop those scientific tools. We’re partnering with the Society of Fire Protection Engineers, which is our professional society to try to bring these tools. And so , we want to train our master’s students, our PhD students, to be able to develop those tools and to use them and make our communities, safer. So that’s really where fire protection engineering can really help. Uh, and then of course there are additional aspects like, first responder safety, we know, we know very well fire how it behaves so we can help the firefighters to be safer when they fight those very difficult fires.

Cain: There’s also a lot of public awareness that is involved in your research and letting everyday people know about the risks of fires and, and what they could possibly do about it. I know you’ve sort of advocated that there are some things that people can do with their properties. Do you wanna talk a little bit about what folks should be thinking about to try to reduce the risk of a wildfire, coming up to their property and their home?

Simeoni: Absolutely. I mean, I think there are two components. I mean, there is the grand public and uh, the need in summary as to be aware of, uh, your exposure and, we can contribute to that. And there is also, the need for deciders to, make the right policy decisions, you know, and to give them support so they can develop the right policy. For instance, we advocated with the state of California to make mandatory in codes and standards measures to clean around your house, especially for the shorter distance about your house, because that’s really a big pathway for the fire to enter your house. So making aware the grand public, but also the deciders is very important. And on top of that, with the research, which is, of course, in the long term we’re trying to build the scientific base and the scientific knowledge. So, we give the information to make sound decisions. Um, one of the projects we have, which is led by, uh, my colleague, professor Urban, is about, really understand the exposure of structures to the fire coming from the wildlands. And so, we’re doing tests in our labs, where we have, vegetation or mock vegetation actually burners, uh, burning. And we’re looking at their ability to ignite, structural elements. We’re doing that with a burning pieces of vegetation and creating embers that will deposit on the structures and accumulate and then ignite fires. And we’re looking at how these processes happen to help make those decisions. So I will make an analogy here. And it’s, like first aid. You know, when the catastrophe happens, you need to know how to react and that can save yourself, your family, your neighbors. Uh, it can serve your property. For instance, leaving your house and closing all doors and windows when you’re evacuating, making sure that you have, no combustible material that is laying around like, or close to your house or around your house, like firewood, toys, things like that. So there are some things, that are simple measures and simple actions that you can take and that can make you safer. And one of the problems we have is that we live in a very different society. We’re not in the areas where we’re close to the wildlands or the woods, I would say, we don’t have people who are used to living in the woods and know exactly what is the fire season, when it’ll come, how to even light counter fires like it was done in the 19th century. We have people having secondary homes. We have people living there and we have never seen a wildfire close. So knowing how to react, knowing what are the basic steps to take to protect yourself and your family. And it includes also smoke exposure. You know, if you have asthma, if you have some condition that makes smoke very, very bad to you, smoke from wildfires, even if sometimes it smells good, it’s plenty of very bad chemicals, so you need to minimize your exposure, the exposure of your kids, and all of that. So knowing about these basic things will help you to protect yourself, protect your family, and make everybody safer. But the best resources here are from the National Fire Protection Association. I would recommend, for people to look at the NFPA, Guidance, which is called Firewise. It’s a program to make your, uh, houses safer. I mean if you’re in California, there are plenty of rules and regulations and Cal Fire can even visit your house to give you recommendations for the best things to do. Uh. Uh, but again, it’s getting back to the basic things. When there is a fire risk, don’t leave fuel around your house. In, many places, it’s very problematic to have a lot of shrubs, which are small trees. Their branches will touch your house. It’s a problem. So vegetation management is a big aspect, but also the external envelope of your house, because there is a wildfire, even if you have a bunk and you have only one window and you leave it open, that’s a path for the fire to come in. So you have also to be careful about your vents, about your windows, your door, your garage door, and make that fireproof. There is guidance from NFPA. There are codes and standards from, for buildings, which are helping of course, we’re less strict and restrictive about that in Massachusetts than we would be in California. But there is a good basis.

Cain: That’s a really good point that you make that codes and standards are gonna be a little bit different based on different states and different parts of the country. Um, certainly there seems to be an increasing awareness in Massachusetts the last few years about wildfires because of, uh, the increased number of acres burned in this state, as well as some of the incidents of smoke coming in from other parts of the country, uh, seemingly on a frequent basis. I’m wondering what’s your sense of the landscape of wildfires, that we’re seeing and why it’s so important at this particular moment in time to stay focused on this?

Simeoni: There are two points here. So first, even in a normal context, it’s not because we don’t have many fires in Massachusetts and in the Northeast in general and other parts of the country that they’re not happening. The return time for wildfires in the Northeast is 70 years, and the last big wildfire we had was in 1946 in Maine, and it was a very large wildfire that was quite destructive. We’re due in a way, you know, because it was over 70 years ago. So already in a normal context, we know that fire is gonna come back. Now with the climate change, but also the urban sprawl, you know, the increase of what we call the wildland urban interface, before the WUI, we have more points of contact with the places that are, possibly be burning in the future. And so, having a good awareness of, what a wildfire could do and how we can protect ourselves I think is important because it’s not, because it’s not happening very often and it didn’t happen in the past, that it’s not gonna happen in the future and even more often. And then, there is the smoke aspect. Our vegetation and, uh, our climate, because we have the tendency to be more humid than Southern California, for instance. You have fires during the day and then the smoke is accumulating at night until the morning and when the day is gonna kind of clear the atmosphere and so we have a big exposure to smoke. We’ve seen that for the October fires in Massachusetts where the smoke was really laying low in the valley and that’s a big exposure especially for the population at risk. And so we need to close our windows, get good HEPA filters for the air conditioning and minimizing the exposure to smoke. It’s very important in terms of public health.

Cain: You’ve talked a lot about the different partnerships and various research. I’m wondering if you have an example, uh, that you’re really proud of where some knowledge that you produced in your research resulted in some concrete safety changes.

Simeoni: Yeah. So, we have this strong collaboration with the New Jersey Forest Fire Service. It’s spanned almost a decade and it went through our partners in the Forest Service. We have a few researchers who have their experimental forest in New Jersey and they have this great relationship with the New Jersey Forest Fire Service. So, through them and their researchers we were able to do research, especially on embers and firebrands released by the fire and in New Jersey you have what’s called the Pine Barrens, which is a national forest. There are a lot of pines and they burn quite a lot. It’s the most intense fire regime that we have on the east coast of the US. And uh, so of course there are a lot of people in Jersey and around that and so it’s, it’s very densely populated. And so the smoke and the fire can really threaten a lot of people. And so they have a very intense prescribed burn program where they burn vegetation before the fire season to avoid the fires, to explode and become out of control. Through our studies we were able to show that the prescribed burns, because they’re scorching the trees and the vegetation and the bark of the trees, was decreasing the production of embers and firebrands and so decreasing the exposure of, the, buildings and the structures, around the forest. And, uh, very proud of that because it helped them to support their program, which is a big success for the eastern US.

Cain: Well, you’ve definitely made the case for the need to have this knowledge and to spread it. I imagine you need more students to come in and continue this research. Why would you encourage somebody to, enter this field of study?

Simeoni: Oh, I think it’s very simple, you know, and it’s very going to the core of what we do at WPI. We’re saying that we’re engineers and, of course we, uh, are very technical, but we want our engineering to help the world and have a meaning and change the world, and that’s what we can do with wildfires. It’s a global problem. It’s also a problem which is impacting a lot of people in the United States and all around the world. And, uh, we need people with the right skills to provide the engineering solutions to make our societies more resilient to fire, because fire is not gonna go anywhere. Fire is here to stay and everything is pointing at the fire problem worsening. So if you really want to change the world, if you really want to help make people safer, make their property safer, and help the environment, I mean, you will have a great career in this field.

Cain: Well, Albert, thanks very much for taking the time to talk with me about your work and, how you’re bringing it out into the world.

Simeoni: Thank you. My pleasure.

Cain: Albert Simeoni. is a professor and head of WPIs Fire Protection Engineering Department. You can learn more about Fire Protection Engineering research and academic programs by visiting our website – wpi.edu. While you’re there, search “wildfires” to read our explainer with answers to frequently asked questions about wildfires. This has been The WPI Podcast. Join us again for our upcoming episode that will explore how WPI researchers are studying what happens to indoor air quality when wildfire smoke gets into homes. The work is happening in our Civil, Environmental, and Architectural Engineering Department with a focus on children’s sleep health and the absorption of smoke in building materials. You can hear more episodes of this podcast and more podcasts like this one at wpi.edu/listen. There, you can also find audio versions of stories about our students, faculty, and staff -- everything from events to academic projects. Please follow this podcast and check out the latest WPI News on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Amazon Music, Audible, or YouTube Podcasts. You can also ask Alexa to “Open W-P-I.” This podcast was produced at the WPI Global Lab in the Innovation Studio. I had audio engineering help today from PhD candidate Varun Bhat. Tune in next time for another episode of The WPI Podcast. I’m Jon Cain. Thanks for listening.

Degrees

Master's in Fire Protection Engineering

Make the World a Safer Place from Fire

[...]PhD in Fire Protection Engineering

Take your place at the frontline of a global movement to design a safer world with WPI’s internat

[...]