Imagine you’re on a roller coaster at 20,000 feet in the sky, or higher, and repeatedly enduring the sensation of your stomach dropping, all while overseeing a scientific experiment.

That was the experience PhD candidate Regan Krizan had on Oct. 28 in Bordeaux, France. Krizan, a student in the Department of Mechanical and Materials Engineering, flew on a parabolic flight, sometimes known by the nickname “vomit comet,” to conduct a materials science experiment in zero gravity.

Krizan experiencing zero gravity during research flight.

“I always wanted to be an astronaut growing up, and this is about as close as I can get,” says Krizan. “I am very excited that I had this opportunity so early in my research career.”

The parabolic flight travels up and down several times on a trajectory resembling an arch, providing 22 seconds of zero gravity at the apex, creating a critical element for scientific research that can’t be achieved on Earth.

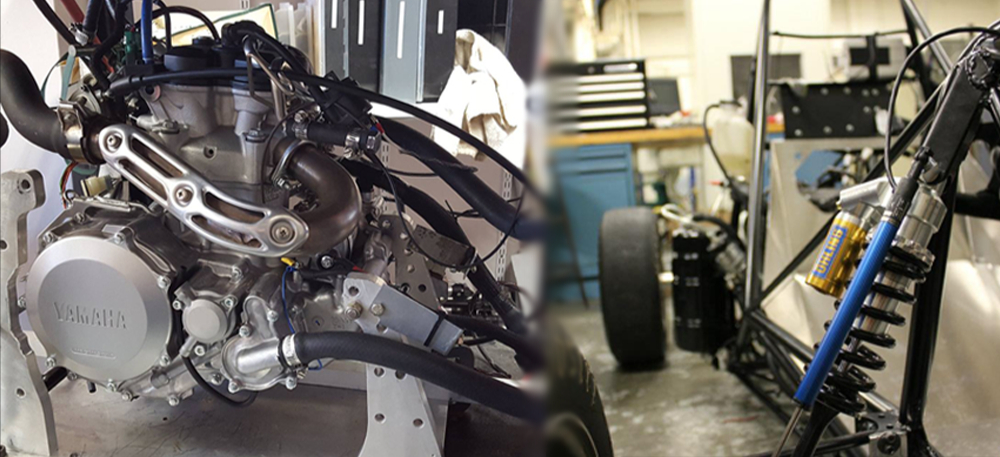

The experiment, which seeks to understand what happens when metal is melted, was conducted in an on-board electromagnetic levitator. Essentially, by sending electrical currents through copper coils to create an electromagnetic field, a metal sample can be made to levitate inside a chamber in zero gravity while the metal is heated to melt. This allowed Krizan and Gwendolyn Bracker, an assistant research professor in the Department of Mechanical and Materials Engineering and one of Krizan’s faculty advisors, to observe how an iron-copper alloy separates into two distinct liquids when melted, similar to how oil and water don’t mix.

“We are investigating a rare case in which the fluid flow can be visually observed due to a two-phase liquid separation in the iron-copper system,” says Krizan. “Microgravity makes isolating thermophysical properties of a liquid sample possible. These conditions can only be met on the International Space Station or on a parabolic flight.”

The experiment provided Krizan and Bracker with high-speed video and temperature data that will help the researchers better understand fluid flow. The pair hopes their study will lead to improved fluid flow models that can simulate how liquids flow and solidify.

Inside the plane used for the zero-gravity flight.

“The experiments on the parabolic flight are integral to validating fluid flow models to aid in data analysis for electromagnetic levitation and applying the results to the manufacturing industry,” added Krizan. For example, the models can allow for reduced trial and error and improved efficiency in making molds for casting.

“Understanding how metallic melts behave is critical for manufacturing, casting, and additive manufacturing,” says Bracker, who traveled with Krizan to France and watched from the ground as her advisee and the experiment were on the flight. “Many metallurgical processes originated in historical processing and require a greater understanding of the fundamentals to improve. By building better models we can support the development of more efficient processing and production.”

Bracker (second from left) and Krizan (fourth from left) with research collaborators from the Institute for Frontier Materials on Earth and in Space at German Aerospace Center (DLR), Photo: Mélissandre Lacaille for Novespace

Krizan and Bracker’s research, in conjunction with the German Aerospace Center (DLR), was one of more than a dozen experiments on board the parabolic flight, which the European Space Agency makes available to scientific researchers. Krizan is co-advised by Bracker and Robert Hyers, the George I. Alden Chair of Engineering and head of the Department of Mechanical and Materials Engineering.

In addition to the feeling of weightlessness, Krizan and others on board experienced hypergravity during the climb and descent. “I wasn’t that scared about how the flight would affect me going into it,” adds Krizan. “I handled the physical challenge well, and it was a great experience that is so meaningful to my research.”