Record-high floodwaters that inundated parts of the South last week are receding, but Rajib Mallick, professor of civil and environmental engineering, says hidden flood damage could lie beneath the surface of the roadways months after the floodwaters have gone.

“Public works leaders across the South need to do everything they can to evaluate the condition of the roads,” says Mallick, a researcher at WPI’s Pavement Research Laboratory. “The structural integrity of these roads may have been compromised due to the historic flooding.”

According to published reports, more than two million people across Louisiana, Mississippi, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Tennessee, and Texas have been impacted by the floods, which have resulted in six deaths and more than 6,000 homes damaged.

Mallick and his research team have significant experience in evaluating the integrity of the nation’s roads. In April 2014, WPI—in tandem with University of New Hampshire—received a $125,000 grant from the Federal Highway Administration to conduct “flooded pavement assessment” in various parts of the country. The grant calls for advising state departments of transportation and the Federal Highway Administration about the conditions of flooded roadways. Mallick noted that WPI has been conducting a significant amount of regional work for state departments of transportation in New England since the late 1990s.

According to Mallick, universities and research institutions across the United States need a significant amount of investment from the federal government to develop better road materials, construction, and maintenance processes.

“For the past several decades, the number of trucks and other vehicles has gone up steadily and significantly, but the number of new roadways built has been miniscule,” he says. “This means significantly added stress on existing roadways. And this stress gets multiplied with the effect of extreme events such as flooding, and we do expect more flooding in many places in the future due to climate change.”

In an effort to evaluate roads, WPI leaders use a high-tech piece of machinery known as a falling weight deflectometer (FWD), which was obtained via a federal grant in 2005. The deflectometer, which looks like an air conditioning compressor, applies a dynamic load that simulates the loading of a moving wheel, such as a tractor-trailer. The unit sits on a platform that is towed by a van.

The university’s FWD—one of the few owned by a university in the United States—is equipped with multiple geophones, cone-shaped devices that touch the road and measure ground movement. The first geophone measures the capacity of the structure of the pavement and the other geophones can measure the surface, base, and sub-base of the pavement. Ethernet cables are also connected from the FWD to an on-board computer that tells researchers where the “deflections”—or dips under the pavement—exist. Pavement that is in poor condition will show deeper deflections on the computer screen.

“By using the falling weight deflectometer, we are able to figure out if the problem lies in the subgrade, base, or sub-base of the pavement, or in the surface layer,” says Mallick. “Depending on the type of evaluation, we can test miles of pavement in a day and determine if the pavement is good or bad.”

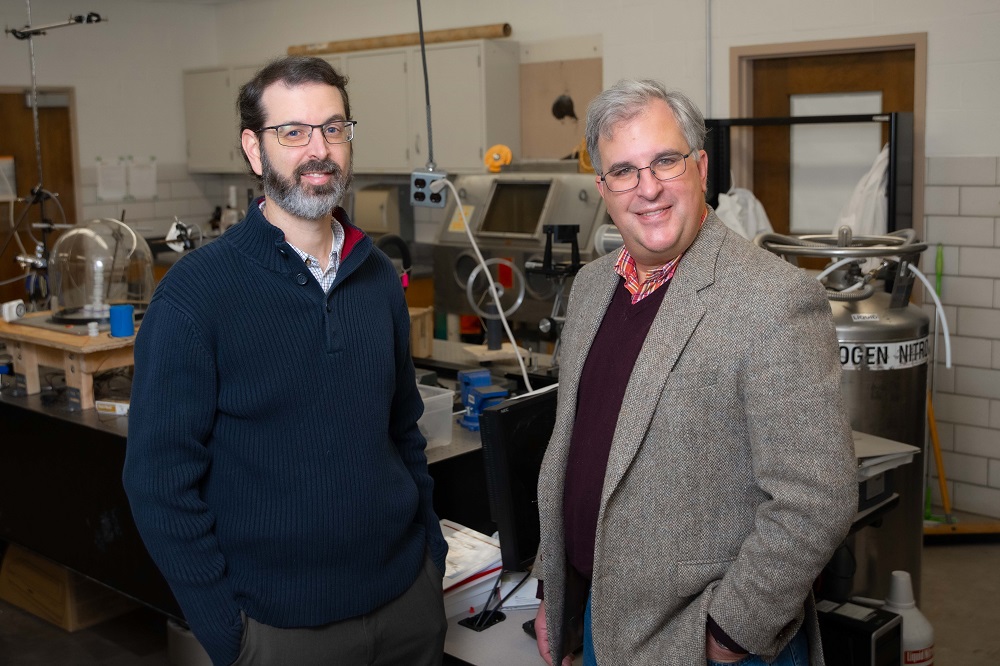

Mallick says the WPI team compares the pre-flooding data against the current flooding data to determine the condition of the roads. Joining Mallick as part of the research team are lab manager Don Pellegrino and graduate student Ryan Worsman ’12.

– BY ANDY BARON