Kymberlee O’Brien

Kymberlee O’Brien has won a grant to investigate microaggressions and physiological stress responses as they relate to minority, international, and other students.

O’Brien, an assistant teaching professor of social science and policy studies, hopes the project will result in follow-up research examining ways people can be educated and informed on the topic of microaggressions as chronic stressors.

O’Brien notes the attention that overt discrimination—due to factors such as race, culture, gender, income level, or bodily ability—has been identified as a chronic stressor in our society. But it’s the seemingly smaller, subtler, and likely ambiguous incidents that can, ultimately, result in poor health over the course of a lifetime. And those, says O’Brien, can contribute to the disparity in the area of health among the disadvantaged in the U.S.

So, what is a micro-aggressor?

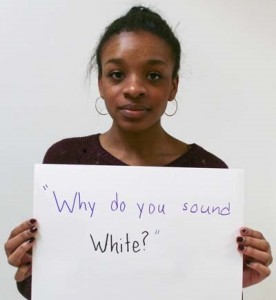

Where overt discrimination is more blatant—a racial slur, different treatment based on cultural differences, inaccessibility of a building to those with physical limitations—microaggression is much less noticeable, outwardly, O’Brien says.

Where overt discrimination is more blatant—a racial slur, different treatment based on cultural differences, inaccessibility of a building to those with physical limitations—microaggression is much less noticeable, outwardly, O’Brien says.

“They are more subtle mechanisms and may be very difficult to home in on,” she says. They may even mask themselves as a back-handed compliment.

An example, she says, is saying to someone, “You speak English so well,” or “What are you?” in inquiring about someone’s country of origin, when they are, actually, a human being. “‘You look so exotic; what are you?’ while not meant to be offensive, comes from a need to categorize very quickly,” says O’Brien. “It’s something we do.”

Another example of a micro-aggression, she adds, is if someone says, “Oh, don’t worry, I’m color blind.” It is still calling attention to the difference in color between the speaker and subject, just in a more camouflaged manner, she notes.

The effects of such microaggressions include a cardiovascular response, change in blood pressure, and an increase in the stress hormone cortisol. Severity depends on how frequent such microaggressive interactions are happening. O’Brien also points out that waiting for the next one to occur is a stressor all its own.

“Every day it’s a fight-or-flight response,” she says. “It’s a serious state of toxic alertness,” just wondering when the next micro-aggression will occur, where, and with whom.