Time and again I’ve longed for adventure

Something to make my heart beat the faster

What did I long for? I never really knew.

— All the Things You Are (Jerome Kern, Oscar Hammerstein II)

Frederick Bianchi, left, and Rich Falco

Louis Armstrong once said the essence of jazz is, “never play anything the same way twice.” Indeed, free improvisation is at the heart of jazz and is what distinguishes it from many other musical forms, including classical music. It’s why each performance of a jazz standard like All the Things You Are constitutes a new creative adventure for the musician and a unique experience for the listener.

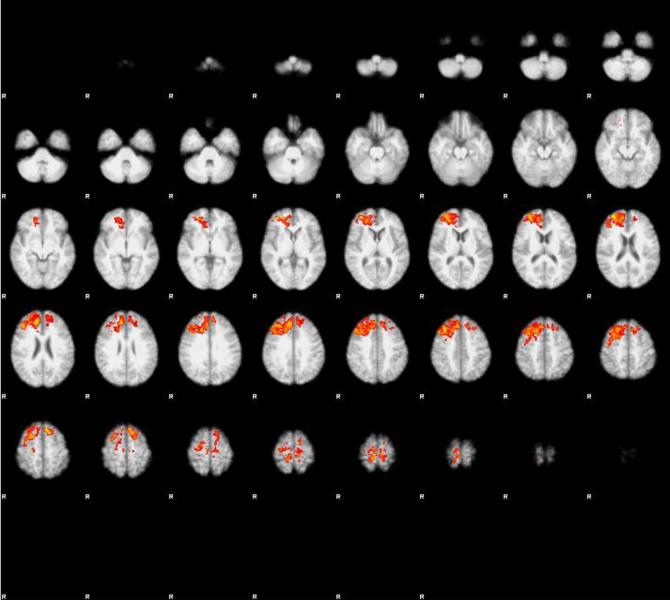

While improvising is clearly a distinct creative process, does it also reflect a unique state of mind? And if so, can that state be identified in the way the brain behaves during musical improvisation? And if one can connect the improvisational process to patterns of brain activity, can that knowledge help educators teach students to be better improvisers and more confident performers?

These are among the questions that drove two music faculty members at WPI to become brain researchers. For jazz guitarist Rich Falco, director of jazz studies at WPI and founder of the Jazz History Database, that transition began when he first noticed a set of common behaviors in musicians playing improvisational jazz.

“They have a relaxed posture, slow breathing, and a sort of calm,” he says. “The tension seems to drain away as their focus shifts internally. I like to say, they’re ‘in the zone.’”

Composer and musician Frederick Bianchi, director of computer music research at WPI and developer of music technology, including the Virtual Orchestra, also has observed and experienced the zone. “In the zone, action and awareness merge,” he says. “Inner analysis is bypassed and the brain’s predilection to micromanage is denied. Time becomes suspended, ideas begin to flow, and the performance unfolds without effort.”

By chance, one of Falco’s and Bianchi’s colleagues, Karl Helmer, PhD, is assistant professor in radiology at Harvard Medical School and assistant in research at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH). He conducts cognitive research using the MRI scanners at MGH’s renowned Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging.