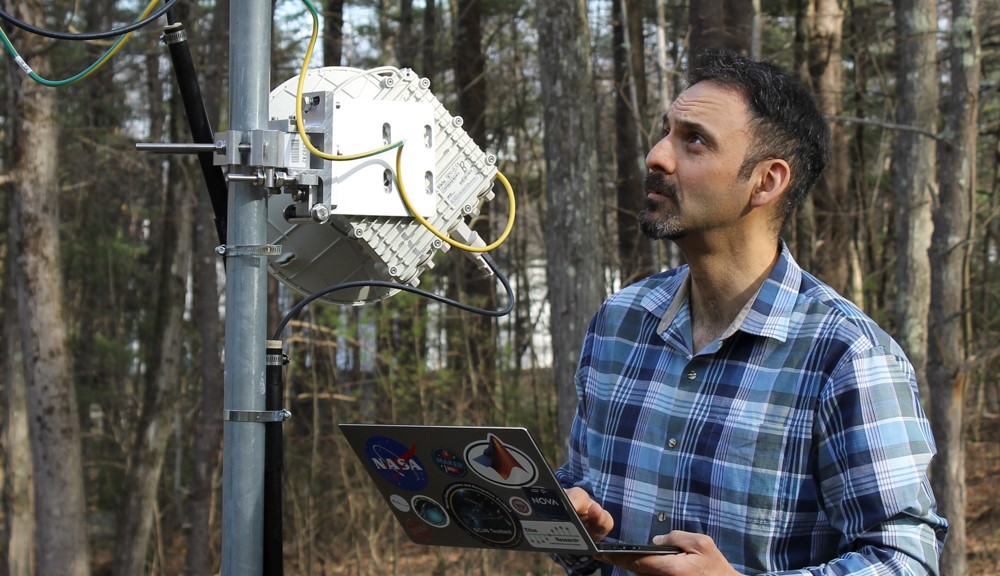

Rob Gegear, pictured, is working with fellow

researchers Alex Wyglinski and Elizabeth Ryder,

on a three-year $300,000 NSF grant.

Things are buzzing at WPI these days. Quite literally. An interdisciplinary team composed of electrical and computer engineering and biology professors is exploring how we can create better wireless networks for connecting vehicles—and, therefore, making driving safer—by studying how bumblebees make decisions as they forage. Working on the creative project is Alex Wyglinski, associate professor of electrical and computer engineering; and professors Robert Gegear and Elizabeth Ryder in the biology and biotechnology department. The professors recently received a three-year, $300,000 grant from the National Science Foundation to pursue the research, which is formally known as "Enhancing access to the radio spectrum."

By studying bumblebees, Wyglinski, Gegear, and Ryder are aiming to create a novel framework for enhancing the performance of dynamic spectrum access (DSA)-based vehicular networks.

And the research is generating significant media attention in leading trade media outlets. On Dec. 3, IEEE Spectrum included a story titled "Cars Could Follow the Flight of the Bumblebee," which stemmed from an interview Wyglinski had with freelance science/technology writer Neil Savage. "Just as the bees look for flowers with the best nectar supply, the radios would look for channels with the highest signal quality," Savage wrote.

Earlier, Wyglinski, the principal investigator, spoke with Motherboard contributing writer Melissa Cronin about the project. In that Nov. 15 story, titled "Bumblebees Are Teaching Smart Cars How to Drive," Wyglinski notes that there is significant value in studying bumblebee behavior. In fact, he said, you can’t rely solely on computer models.

"The issue with using mathematical equations is that mathematical optimizations make a lot of assumptions," Wyglinski told Motherboard. "They are optimal only under ideal circumstances. But a bumblebee works in the real world."