While the news brings near daily reports of compromised data and new hacking successes, young students might not realize what it means or understand how they can change it. A camp at WPI is changing that.

For the third summer, WPI is offering a GenCyber Camp as part of its Frontiers summer camp series. Suzanne Mello-Stark, computer science professor, says the camp raises awareness of cybersecurity careers and gives high school students the knowledge of both personal and professional online safety.

GenCyber camps are funded by the National Security Agency (NSA) and are held at institutions nationwide, but it’s especially fitting at WPI where interest in cybersecurity is high. The 13-day camp, which fills up every year and attracts participants from as far away as San Francisco, introduces students to ideas from passwords and online privacy to the ethics of cyber issues.

The potential impact for a shortage of cybersecurity professionals is alarming, and it’s something younger students aren’t aware of. The news of hacks and data breaches might be on the front page for adults, but that doesn’t necessarily make it a hot topic for students. “The kids don’t hear it in their own worlds,” Mello-Stark says. “They are often surprised by what I tell them.”

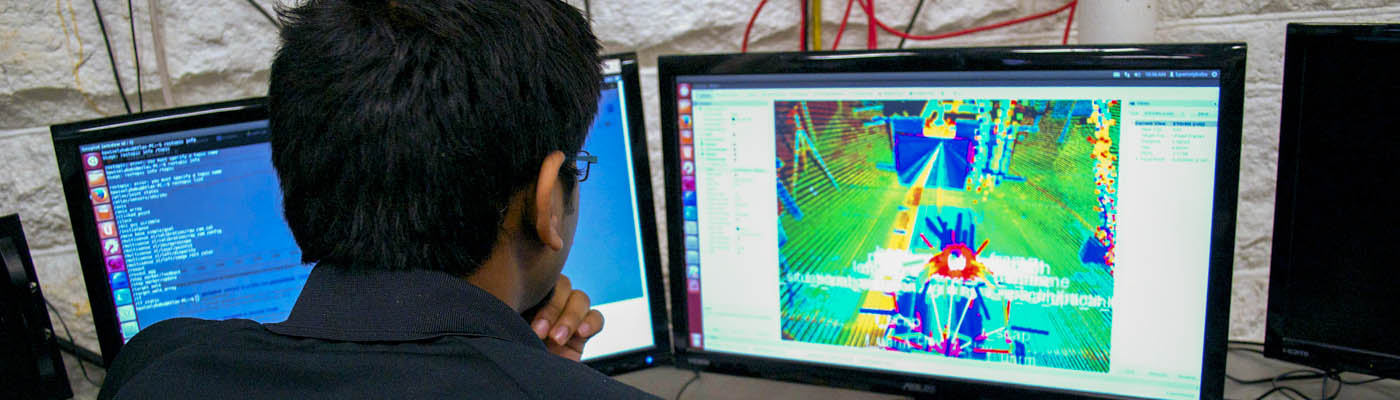

With an awareness activated by the camp, the students get excited when they learn about hacking techniques (albeit in a closed and protected virtual system developed for the camp) and how ”the good guys” try to stop “the bad guys.” But Mello-Stark explains clearly why the students need to be able to do the very thing they are trying to prevent. “To know how to protect something, you have to know how to break it,” she says. That’s when the ethics of cybersecurity comes into play—the students learn the responsibility of having the knowledge.

Students build binary bracelets.

Students build binary bracelets.

In addition to the real-world, hands-on projects, the camp, which hosts 20 participants from July 23 to August 4, offers up information in fun ways. “There are lots of cool things,” says Mello-Stark. “We teach them about cryptography, and I run the Amazing Cryptography Race. We use invisible ink and they learn how to do crypto. The students work in virtual environments and gain some hands-on computer science experience as well."

“You have to have a background in computer science before you can understand what the cybersecurity problems are, so we try to give them some hands-on experience while they’re here,” she says. “We know that in many schools, computer science isn’t taught as early as other sciences, like biology, and students are hungry for it.”

While a main goal of the camp is to generate interest in cybersecurity as a college major and ultimately as a career, a broader awareness of cybersecurity issues is important for everyone, says Mello-Stark, who notes that of course not every participant will go on to have a career in cybersecurity. “It’s interesting to see where they go,” she says. “After the camp, I am sure they have a little more understanding about privacy and how to stay safe online, and what job opportunities are out there. If they decide not to go into cybersecurity, that’s fine. We want them to know about it and make an educated decision.”

Several guest speakers came to camp last year, and Mello-Stark is hoping for a return this summer. Last year, two FBI agents regaled the students with a 90-minute Q&A. The agents talked about some cases they have worked on and how they have to stay fit for their jobs. A cybersecurity expert from MITRE, along with Nicholas Brown ’16, ’17 (MS CS), who was then a WPI grad student interning at the company, came to talk about bio-behavioral metrics.

Students take a break from the day’s

Students take a break from the day’s

activities.

This year, Mello-Stark will have an assistant helping her run the camp—Wesley Swenson, a math teacher at Tahanto Regional High School. In an effort to broaden the camp’s message and impact in the region, Swenson will develop lesson plans that he can then take back to use in his own classes. Even the simple tips will make a big impact, Swenson says. “I took an informal poll about passwords with some of my students, and most of them are using the same password for everything,” he says. “I am excited to take back some of the coding for the students, but just to help them with awareness is very relevant… Awareness of security and where the dangers lie.”

And that is exactly what the camp’s mission should include, says Mello-Stark: Many high school teachers don’t have cybersecurity experience and, therefore, most high school students don’t learn cybersecurity as part of their typical curriculum. Because of these varying levels of capability, the camp might have beginner and advanced students simultaneously. Activities will include learning about parts of a computer and how the computer works, operating a simple Python program, understanding binary and hexidecimal, and building a Raspberry Pi.

While the interest is often in the more spy-like elements of cybersecurity, the camp really delivers accurate information about how to be safe online and piques interest in the field, with the ultimate goal of increasing the number and the diversity of qualified cybersecurity specialists. Teachers who attend improve their teaching methods and content thereby sparking interest among their students, but also among themselves.

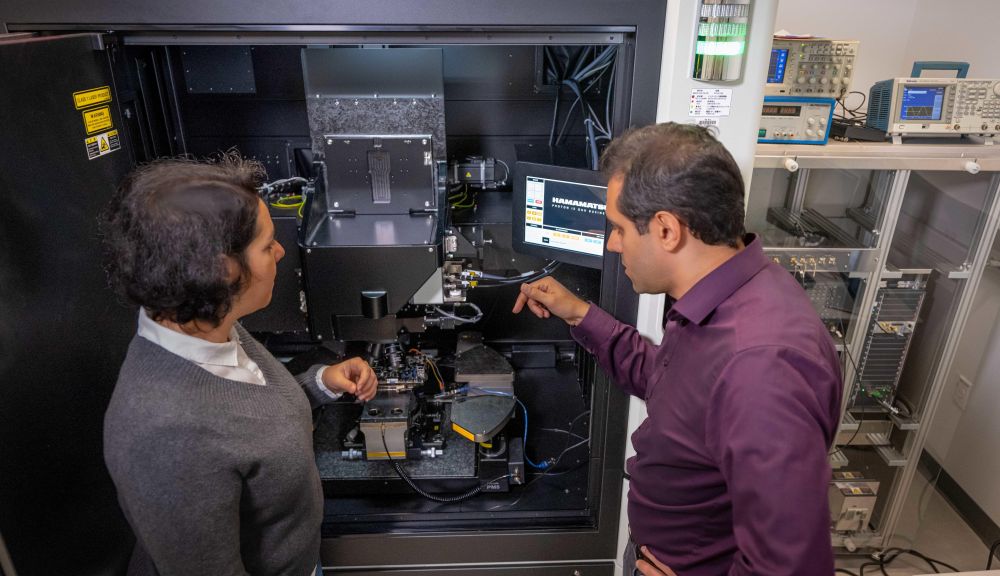

With funding through the National Science Foundation, WPI also offers the CyberCorps: Scholarship for Service (SFS) program in cybersecurity that helps bring a well-educated workforce to an industry that needs workers. Now in its third year, the program is available for rising WPI juniors and seniors and graduate students who want to pursue a career in cybersecurity. In exchange for tuition and some reimbursements for things like books and travel, and annual stipends of $22,500 for undergrads and $34,000 for grads, the recipients agree to work as summer interns and then work in government (the federal level is preferred, but not required) after graduation for as many years as the scholarship was received.

Brown, who was also a SFS participant, says the SFS program helped him decide to pursue graduate level work in cybersecurity. “Now that I’ve graduated, I’m going to work as a cybersecurity researcher at the MITRE Corporation, one of the many federally funded research and development centers that we can work at to fulfill our service requirement.”

Alexander Witt ’15, ’17 (MS CS), says the SFS program helped him professionally and financially. “SFS offered the opportunity to learn more about the field of cybersecurity and identify areas of interest,” he says. “Additionally, the commitment required by the program provided valuable insight into employment offered by the public sector.”

Drawing interested students into cybersecurity will certainly enhance their career opportunities, but also will have a much wider impact. “Without them, we will see more and more hacks and not be able to protect our infrastructure,” she says.

With the broad sweep of both the camp and the SFS program, Mello-Stark hopes to raise interest. “It’s critical work, but it’s also really fun,” she says. “You can’t go a day without learning something new.”

- By Julia Quinn-Szcesuil