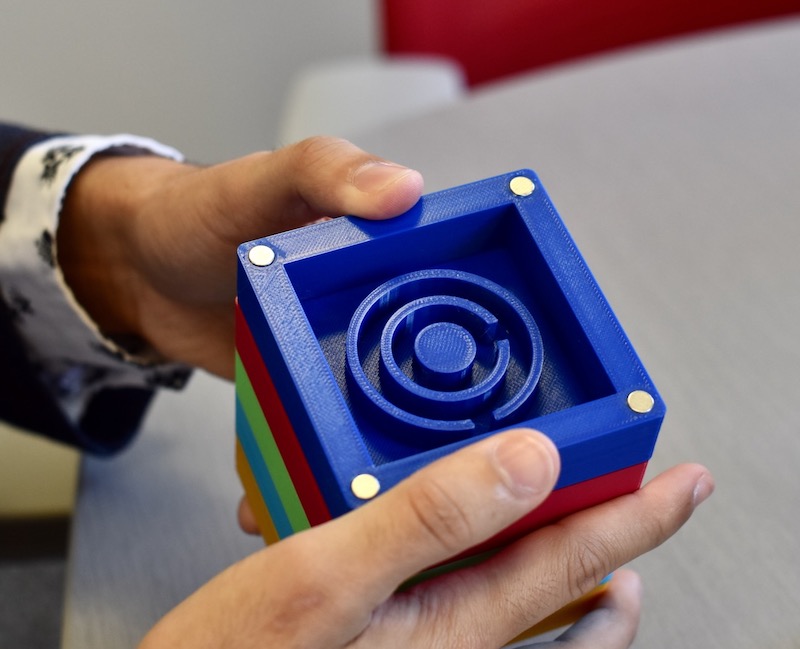

Colorful, straightforward, and compact, the Phase Maze—a stackable, interchangeable series of hand-held games about the size of a box of Pop Tarts—may find its place on toy store shelves and in online shopping carts some future holiday season.

Dreamed up in a Chicago high school by Maanav Iyengar ’23 and eight close friends, Phase Maze is an addictive game that requires users to guide a ball bearing through intricate mazes of varying difficulty. Its origin story follows the familiar narrative of scrappy start-ups: a brilliant idea, a blur of all-night work (in this case, 3D printing in a basement), jockeying to get the product on retailers’ radar, a satisfying burst of sales, and a gleeful struggle to keep up with orders.

The twist in Phase Maze’s narrative comes courtesy of the partner Iyengar didn’t go to high school with: WPI’s Office of Technology Commercialization.

The office typically helps faculty and grad students bring inventions to market in return for some level of royalties and ownership in the company, but OTC support is also available to undergraduate student inventors, and a growing number are taking advantage, said OTC Director Todd Keiller.

“If we are licensing to an existing company, we get royalties and other fees based on success,” Keiller said. “If we license to a startup, we get royalties and equity. There is a steady flow of students through our office, which not only tests their idea for real life commercial potential, but provides a great educational experience.”

Iyengar approached the OTC soon after coming to campus as a freshman.

“I could have started my company myself, but WPI offers me all the protection I need, so when I go to the ‘big dogs’ I know I’m not going to get completely rolled over,” the robotics engineering major said.

“I was inventing throughout high school, and wanted to get patent and IP protection,” he said. “I think WPI’s IP policy is the best in the country, and probably the world. If any school is going to support avid inventors and entrepreneurs, it’s WPI.” Iyengar said he applied to WPI partly because of the OTC’s generous approach to intellectual property.

Keiller said Iyengar has proposed six ideas to the OTC, two of which—the Phase Maze and an innovative solution to sewer issues in developing countries—WPI decided to support.