Faculty Perspective

Guiding them further

Professors Peter Christopher and Bob Hersh discuss their work with sponsors and students at the Albania Project Center, reflecting on how it changes and inspires their teaching and outlook.

What do you personally get out of the experience as a project advisor?

Peter Christopher

Project Center Co-Advisor

Tirana, Albania

We have a new crop of students every year and their experiences are different each time. I like when their eyes open wide at something new, even to taste something they hadn’t tried before. One of them was a very fussy eater and ended up eating fish heads by the end of the project. Students grow in many different ways and it's nice to watch that happen.

Robert Hersh

Project Center Co-Advisor

Tirana, Albania

You get to see the growth of students in a very close-up manner because you see them in ways that most faculty don’t. You notice over that seven weeks how their thinking evolves, how their trust in us changes, and by the end of it—when the projects go well—you realize they have come further than you could have imagined at the beginning. It’s an experience at the close of the seven weeks that feels like something magical has happened.

The Student Experience Over the Life of an Interactive Qualifying Project

What is your role in the work the students do prior to leaving for Albania?

Peter Christopher: I offer them instruction—for two consecutive terms prior to their departure—in the Albanian language, history, and culture. They don’t become fluent in the language, but they learn enough to be polite and to get by.

Is it okay if a project evolves or changes in scope over time?

Peter Christopher: When the new students arrive at the project center, what they envisioned as their project sometimes takes a little bit of a detour. But that’s a good thing, because that’s what happens in real life and one has to learn to make the adjustments so the project will work.

What's the biggest challenge you see the students facing in Albania?

Robert Hersh: In some cases, they’re homesick. Sometimes they find being in a different environment or listening to a different language difficult. Some students from rural areas are surprised to find how busy a city like Tirana is and they find it is exhausting. On the very emotional level of student need, it can be challenging, but we, as advisors, are attuned to these challenges and we have opportunities to talk with them about how to handle these issues. Perhaps most fascinating challenges are those related to things they hadn’t anticipated. There are no right answers to the problems—the data they think they can get oftentimes hasn’t been collected or is not in the form they can use—and the projects change between when they came up with a project idea and when they are at the project center. They have to show incredible flexibility in the face of these changing projects.

Another challenge encountered at all project centers is figuring out the differences between what the sponsors might want and what we advisors want. Sometimes there’s a research question we’d like them to approach in a rigorous way but the sponsor wants something more applied and practical—both are important to any project. The students become more sophisticated in how they satisfy the requirements set by their advisor in terms of what is an appropriate academic outcome and what might be useful for a sponsor. By the end of seven weeks they typically understand that, but it’s still a big challenge.

How do you assist in helping students overcome challenges they face at the project center?

Peter Christopher: To overcome the challenges, we have the students reflect on the experience itself. In my particular case, I like to plan a cultural learning evening halfway through the term when they share their experiences with others. This helps them express what they are actually going through.

What are the benefits of the IQP experience for the students?

The experience forces students to mature because they have to take responsibility for their own learning. They must be willing to live with discomfort when they find there’s no one overarching perspective that will be the answer to their project. They learn how to work together not just to get a good grade but to take responsibility because the sponsor has a keen need for research on a particular aspect of a problem. They come to understand that it matters not just to that person but to other people. They have responsibility in the larger question, "how do we improve society and how do we improve peoples’ lives?"

Students also benefit from the demands that projects impose on them. They must work together well as a team; they must understand and anticipate the needs of many different people. That they understand the social complexity of a problem is an enormous gift project-based learning gives them. They realize there are many different stakeholders in these issues.

How do you see the students change over the entirety of the Albania project experience?

Robert Hersh: Most fascinating is seeing how they change from the point they first understand their project—even in the term preceding their arrival at the project center—to when they leave for home. When they come to Albania, they often think they will be the experts teaching those that they come across. There is an aspect that with their expertise and technologies they are here to provide people with solutions to problems. That is dispelled quickly when they realize that the people they are working with have incredible knowledge on the project topic. They also realize that the idea of making a difference—a youthful passion we encourage—becomes complicated when they see what is happening in the country they’re visiting.

What happens over the seven weeks is that they become practical visionaries. They understand that the projects themselves raise issues that are complex with respect to politics, culture, and the public or community acceptability of a particular solution. They begin to understand that making a difference is a very difficult process that requires from them the ability to understand social complexity and the need for a long-term commitment to something that their sponsors typically have.

When they arrive they are usually enthusiastic and naïve, and when they leave they have a much better sense about the demands that social reality creates for their project. They know what it means to persist over time to work with people on a collective problem for the benefit of the organization and a wider social good. It’s an incredible learning experience for students that have never had the opportunity to work in a different culture.

How do you define success for the students at the completion of an IQP in Albania?

Peter Christopher: Success, of course, begins with having the students arrive back safe and sound, but beyond that it’s strongly believing that the students have gone through a transformation. This is based on their feedback that this has been a life-changing experience for the better. Their perspective on working in society is different than when they first chose to do the project.

Do you think they continue to reflect on their IQP experience even after they graduate form WPI?

Peter Christopher: Overall at WPI, we do get reflections on their experience over a period of years, some as many as 10 or 20 years down the road. Sometimes they’ll write brief notes of thanks for that experience. It’s very rewarding from that point of view.

Student Interaction with Faculty and Sponsors at a Project Center

How do you interact with the students while at the Albania project center?

Is there an advantage of working with students at a project center vs. in the traditional classroom setting?

Peter Christopher: I offer them instruction—for two consecutive terms prior to their departure—in the Albanian language, history, and culture. They don’t become fluent in the language, but they learn enough to be polite and to get by.

How many students is a project advisor typically advising?

Peter Christopher: I offer them instruction—for two consecutive terms prior to their departure—in the Albanian language, history, and culture. They don’t become fluent in the language, but they learn enough to be polite and to get by.

How much time does a project advisor typically spend with a team at a project center?

Peter Christopher: Being a project advisor is a full-time job, so with six teams, each team on average gets 1/6 of the advisor’s time. We also spent weekends together on excursions. When we have the opportunity for social activities with the students, we learn more about them and, of course, they learn more about us. We sometimes discover talents that the students hadn’t given evidence to before and they sometimes find out talents the faculty may have.

Do the students work directly with the sponsor or through the Albania faculty?

Peter Christopher: Once they are at the project center, the students have the main role in working with the sponsor. The faculty role with the sponsor at the project center is mainly to get an assessment from the sponsor on the progress the students are making.

About the Albania Project Center

When did the Albania Project Center open and how many students have traveled to this center?

Peter Christopher: We started the project center in 2013 with 12 students and three projects. We had 15 students in the second year, 23 in the third year, and 24 this year—and we expect to keep it at 24 in the future. This upcoming year, 39 students are interested in the 24 spots, so, you see, the project center location continues to grow in popularity. This particular location is very attractive to students. They haven’t known much about it before arriving, but the word is getting out that there’s a need for people in this country to have American students come over and give a different perspective on problems, and that our students are gaining a lot from their experience in Albania.

What was your role in the launch of the Albania Project Center?

Peter Christopher: I became interested in setting up a project center in Albania based on some experiences I had many years ago. I spent nine months there in 1992 and 1993 seeing what Albania had done in terms of mathematics during the communist era. This is, of course, because I am a mathematician and I had a grant to study and write about it. So that was part of my motivation for setting up the center. In 2012, a representative of WPI’s global program and I went over to investigate the possibilities of setting up a project center. We did so the next year and it was sort of an entrepreneurial enterprise getting the logistics worked out—housing, safety, special needs for particular students, etc. We were successful in 2013 and have built up from there.

Why is Albania a good project center location?

Peter Christopher: Albania is an ideal project site because it is a developing country with a lot of needs. There are a diverse range of projects to be addressed—environmental, tourism, education, entrepreneurial—all important areas for Albania. Our students know they can make a contribution because it is a small and developing country.

Enjoying a tour of the Berat Castle during a weekend trip to south-central Albania with the entire team of WPI students

A weekend visit to the Valbona region, a beautiful village in northern Albania

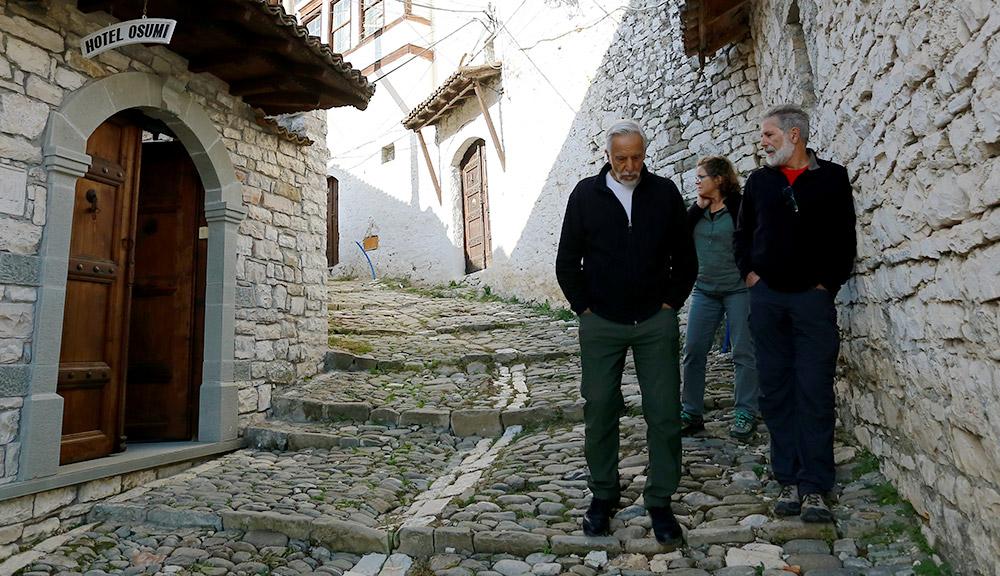

Traveling along the roads in the Osumi canyon region in Southern Albania during a weekend visit to the area

One of the student teams following the final presentation event at the Albania Project Center. Photo by Jason Bruno.

Taking a ferry ride in Northern Albania during a weekend hiking trip

Dancing to Albanian music over dinner with the students while visiting the Berat region during a weekend excursion

Walking the stone streets in the heart of the historic core of Berat in southern Albania

Visiting an old abandoned ex-military base near the Osumi Canyon, the future site of a new adventure resort

Enjoying the Albanian music and dancing with the organists at the Castle Park Restaurant in Berat

A view from the stone walkway inside the Hotel Osumi—a hotel characteristic of homes in Berat with traditional architecture