When a fluid touches a surface that is hot enough to boil it, it is actually removing heat from that surface. All the classic calculations used to predict the rate of heat transfer are based on having gravity as an assumed aid to the process.

Bubbles break free from the bottom of the pot and rise to the surface. In space, none of those theoretical and empirical relations are valid, because gravity isn’t present, and the predicted cooling rates will not be achieved.

Bubbles break free from the bottom of the pot and rise to the surface. In space, none of those theoretical and empirical relations are valid, because gravity isn’t present, and the predicted cooling rates will not be achieved.

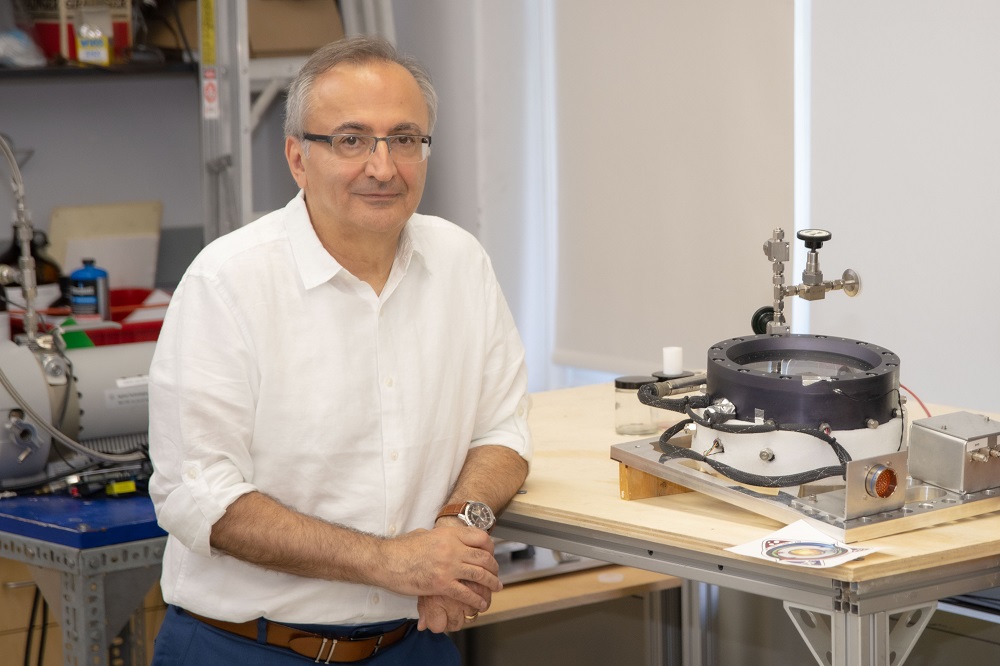

NASA headquarters will provide about $8 million to be used over the next five to six years to study electrically driven liquid film boiling heat transfer in the absence of gravity. Of this amount, about $750,000 will come to WPI and Professor Jamal Yagoobi, George I. Alden professor and head of the Mechanical Engineering Department. He and his team are developing an innovative heat transport technology, driven by the Electro-Hydro-Dynamic (EHD) phenomenon for space applications.

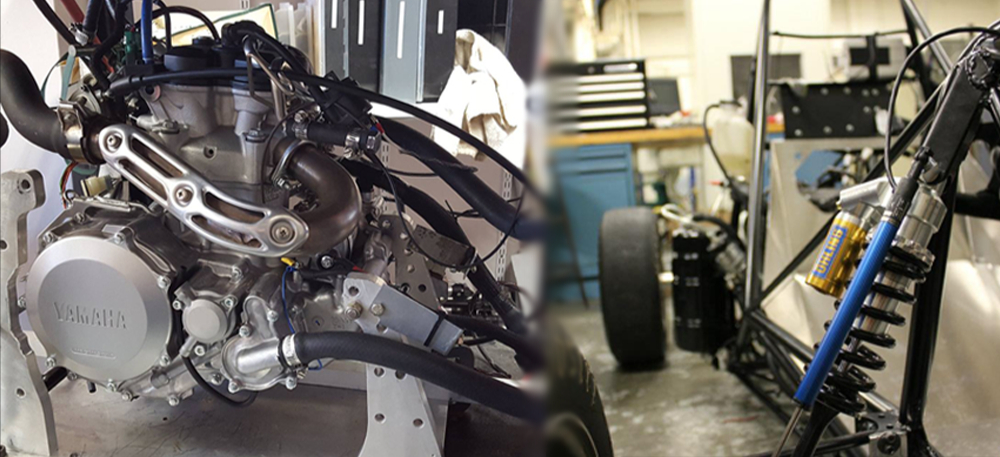

This experiment to be performed on the International Space Station will characterize the performance of this EHD-driven heat transport device. An electric field will pump liquid film toward heated surface and also move the vapor bubbles, thereby replacing the buoyancy to effectively cool the surfaces in space. By making the cooling more efficient, it will improve, for example, the performance of the high-powered electronics that will operate in space.

This experiment to be performed on the International Space Station will characterize the performance of this EHD-driven heat transport device. An electric field will pump liquid film toward heated surface and also move the vapor bubbles, thereby replacing the buoyancy to effectively cool the surfaces in space. By making the cooling more efficient, it will improve, for example, the performance of the high-powered electronics that will operate in space.

Yagoobi is the director of the Multi-Scale Heat Transfer Laboratory, as well as the director of the Center for Advanced Research in Drying. This research will be key in improving many applications in space, and for future terrestrial applications, as well.

The experiments will be built largely at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center outside Washington, D.C., and its Glenn Research Center outside Cleveland. Some of the experiments will be tested this summer by a WPI mechanical engineering PhD candidate as part of her dissertation, and by two undergraduate students as part of their internships at the Glenn Research Center Drop Tower facility.

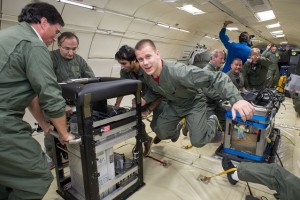

One of the perks of having projects that have been approved and selected for use in the International Space Station is the invitation to ride in NASA’s zero-gravity specialty aircraft nicknamed the “Vomit Comet.” The plane produces 20-second periods of zero gravity by flying in a series of steep parabolas. It can provide varying gravity environments by changing the speed and the angle of the flight, and does this up to 40 times per flight. If needed, the gravity on Mars or the moon can also be simulated.

One of the perks of having projects that have been approved and selected for use in the International Space Station is the invitation to ride in NASA’s zero-gravity specialty aircraft nicknamed the “Vomit Comet.” The plane produces 20-second periods of zero gravity by flying in a series of steep parabolas. It can provide varying gravity environments by changing the speed and the angle of the flight, and does this up to 40 times per flight. If needed, the gravity on Mars or the moon can also be simulated.

Over the course of two years, Yagoobi and his PhD student have tested his projects during 10 flights. He comments that although it was very exciting, everyone was so busy and focused on the experiments, the time on the flights went by very quickly.

The project will not end when the WPI-designed equipment arrives at the International Space Station in 2020. In some ways, that will be the beginning of the next phase of the work. The staff of engineers and scientists here on earth will have to be available to NASA on a 24/7 basis for six months to potentially troubleshoot operations. The experiments will be simultaneously mirrored at the Goddard, Glenn, and WPI facilities. The project is expected to be completed in 2022.

– BY BARRY HAMLETTE