Sometimes it pays to sweat the small stuff. That’s the big-picture takeaway from an initiative started last year by faculty in the Department of Humanities & Arts (HUA) in response to the Mental Health and Well-Being Task Force report.

In this case, the small stuff in question relates to who takes HUA courses—and when. Historically, many 1000-level humanities courses have filled up with upper-level students before first-year students were even eligible to enroll. This left new students either delaying their introduction to certain foundational courses or taking classes in subjects they weren’t passionate about just to fulfill a credit requirement. Both scenarios contributed to students feeling disengaged from parts of their academic journey.

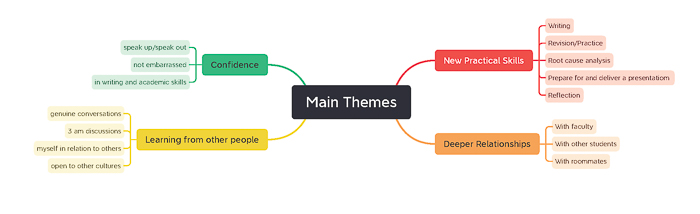

At the same time, as the task force report shows, students struggled to master non-academic skills such as practicing self-care, balancing schoolwork with downtime, and developing meaningful connections with peers. There’s no specific course for these skills and historically students developed them bit by bit as they progressed through their college experience. But opportunities for teens to learn these lessons organically stopped suddenly during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“I come back to WPI day after day because of my students, and it concerned me to know that so many weren’t developing confidence in their abilities,” says Joseph Cullon, professor of teaching and associate department head in HUA as well as co-chair of the Mental Health Implementation Team’s academic subgroup. “I recognized that students needed something additional, but developing a new course or requirement takes a long time. So in conversations with colleagues we decided to change the actual delivery of our courses.”

Cullon recruited 15 HUA faculty members to participate in a pilot program that reserved several introductory-level HUA courses during A- and B-terms in 2022 for first-year students only. None of the actual course content was altered and most of the courses were also offered in other terms, when they were open to all students.