Fermentation gives the world some of its most delicious foods and beverages, like cheese, chocolate, beer, wine, and more.

Now, it can give us a treat for our ears—music.

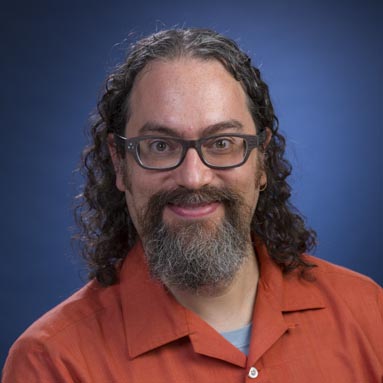

Based on the research of Joshua Rosenstock, associate professor of Interactive Media and Game Development and Humanities & Arts, it turns out that the chemical processes of fermentation can be used to create spontaneous tunes. Rosenstock has built multiple art exhibits called Fermentophone to showcase how fermentation can make music.

“It’s a project I’ve been working on for the past five years,” says Rosenstock, who has a strong interest in food and music. “It’s open-ended art with a serendipitous result.”

And now, this art will be displayed.

Rosenstock and Fermentophone are headed to the Harvard Museum of Natural History on Saturday, Feb. 8, for its I <3 Science exhibit, which is open to the public until Feb. 23. Here, along with two "Meet the Artist" events at the exhibit on Feb. 18, 10–11 a.m., and Feb. 22, 2–3 p.m., Rosenstock will present a multimedia installation of more than 50 “living food-art” jars, created in collaboration with members of the local community.

“It’s an exhibit that invokes all of the senses,” he says.

Fermentophone works like this—first, different fruits and veggies are placed in glass jars and fermented following the time-honored fermentation processes used to make things like sauerkraut and wine. As the fermentation kicks off, the yeast—or bacteria—present in the food chows down on the foods’ sugars, which results in the release of carbon dioxide bubbles. The release of these bubbles—or “burps,” as Rosenstock calls them—creates a tiny sound, which is picked up by underwater microphones. A computer processes the sounds and, with the help of algorithms plugged in by Rosenstock, electronic music is created.