Better bioavailability, greater potency against the malaria parasite, and a built-in shield against resistance make DLA a promising candidate for the next frontline antimalarial medication. But there are other reasons Weathers and an international alliance of scientists, doctors, and non-governmental organizations are enthusiastic about Artemisia.

For one, the plant can easily be grown where malaria is prevalent. And the processes involved in transforming it into a drug can become local business. And without the high-end pharmaceutical manufacturing practices needed to extract, purify, and package artemisinin, the cost of DLA will be far less than ACT. In fact, it is a therapy tailormade for the poor populations who most need it.

Lucile Cornet-Vernet, founder of La Maison de l’Artemisia in Paris, goes a step further, promoting Artemisia, in the form of tea infusions, as a home-grown malaria remedy. An orthodontist, she first learned about Artemisia when a friend who contracted a near-fatal case of malaria on a trip to Africa used tea infusions to cure himself.

Today, Cornet-Vernet’s NGO works with agronomists to select Artemisia variants well suited to the local soils and climates, and sets up centers (42 in 20 countries, at last count) to teach people to grow the plant. “Everywhere, we start small,” she says, “with just one person, then it grows exponentially until we have hundreds.”

Like many advocates for Artemisia, she says she is frustrated with major global health organizations, particularly WHO, which continue to promote ACT over Artemisia. “We believe we will succeed, because we know it is effective,” she says, “but we still have a problem, and it is WHO. They have to be convinced.”

Convincing WHO will take good science, she says, and her interest in the science of Artemisia therapy led her to Weathers. Cornet-Vernet and Weathers agree that, as important and groundbreaking as Weathers’s research on DLA has been, it will take more than the accumulation of positive findings to sway the skeptics. “WHO wants to see good, well-controlled clinical trials in peer-reviewed journals before they are even going to think about Artemisia,” Weathers says. “That is our goal, to get those out.”

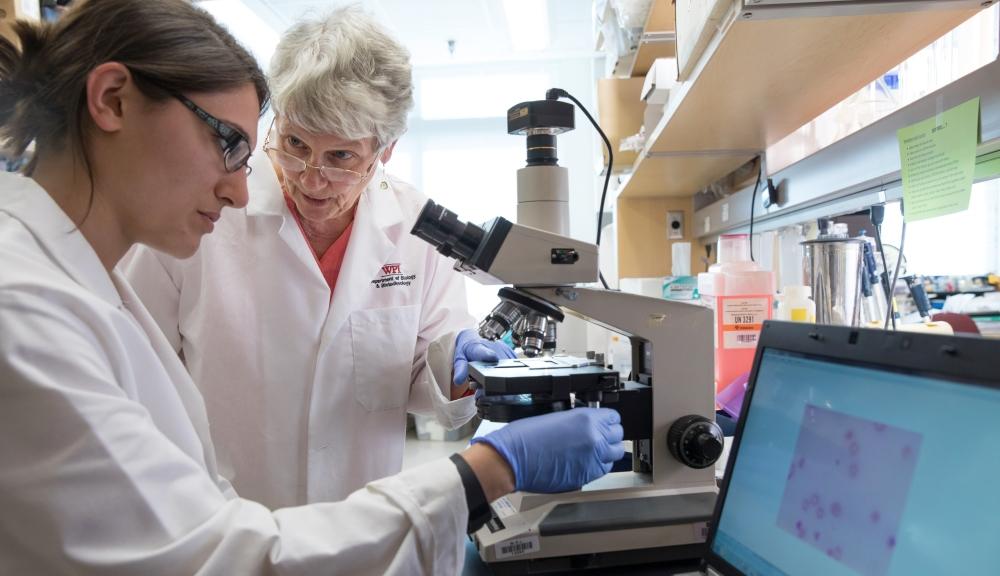

The results of one such trial was recently published in Phytomedicine, the leading journal on plant-based medicine. It was co-authored by Cornet-Vernet and Weathers, along with an international team that also included Melissa Towler, a postdoctoral researcher at WPI who has been studying Artemisia with Weathers for several years, and Chen Lu, a recent PhD graduate in mathematical sciences.

The study compared the efficacy of tea infusions of Artemisia annua and Artemisis afra to ACT in a group of over 950 malaria patients in the Democratic Republic of Congo. In a nutshell, the Artemisia teas (even those made with A. afra, which produces almost no artemisinin) were much more effective than the current drug in clearing parasites from the blood, and did so faster (and with no apparent side effects).

“The ACTs failed miserably,” Weathers says. “At the end of the treatment period, many of the patients treated with ACTs still had parasites, while virtually none of the patients who’d consumed the tea did. We don’t fully understand why the ACTs did so poorly, but it was very striking.”

Just as significant, unlike the patients who’d received ACT, those who’d consumed the Artemisia tea infusions had no detectable gametocytes in their blood after treatment. A mosquito biting these individuals could not ingest the parasites needed to continue the life cycle, effectively breaking the cycle of infection.