Dmitry Korkin

Kpetchehoue Merveille Santi Zinsou

WPI Professor Dmitry Korkin and researchers in Senegal are using a unique type of artificial intelligence (AI) to develop a tool that could not only help pathologists in tropical regions diagnose skin diseases, but also show those pathologists how AI makes its decisions.

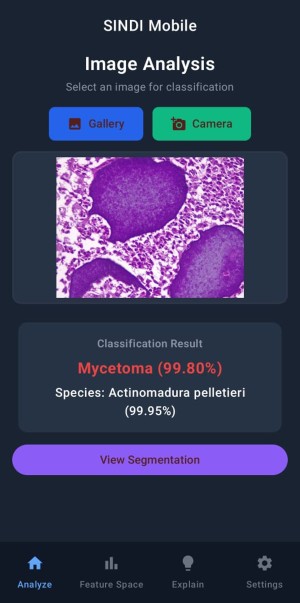

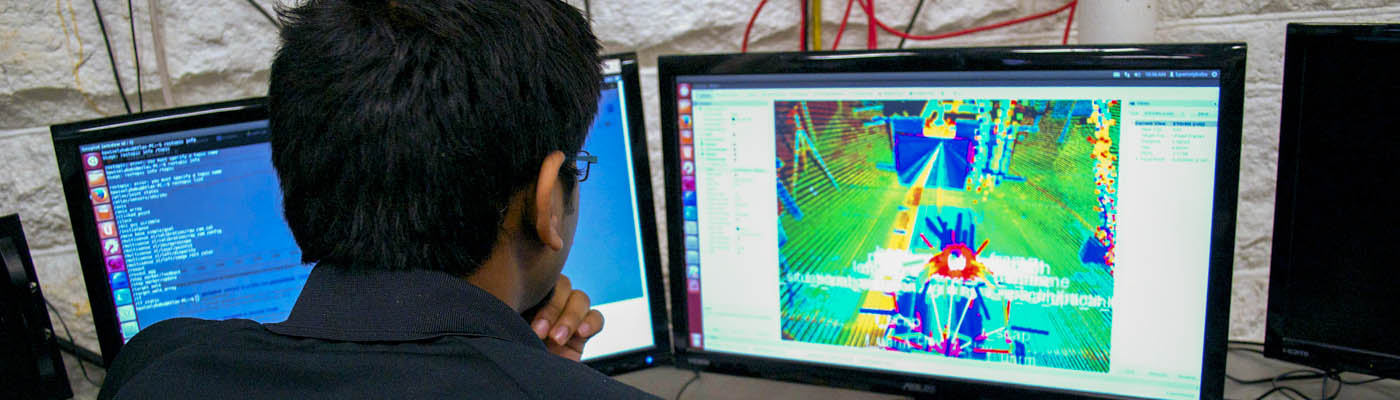

The research involves explainable artificial intelligence (XAI), an approach that draws back the curtain on AI to reveal the processes of machine-learning algorithms. The researchers say their XAI tool can analyze skin specimen images to identify pathogens that cause mycetoma, a disease often found in rural parts of Asia, Africa, and Latin America where medical and technical resources may be limited.

“AI can feel like a black box holding something that is very difficult to comprehend,” says Korkin, the Harold L. Jurist ’61 and Heather E. Jurist Dean’s Professor of Computer Science. “With XAI, we can build a tool that will help diagnose skin diseases and provide down-to-earth explanations about the entire decision-making process.”

Known as SINDI, for Skin INfectious Diseases Intelligent framework, the XAI tool evolved from the work of Kpetchehoue Merveille Santi Zinsou, a PhD student who arrived at WPI in 2024 for a year in Korkin’s lab under the Partnership for Skills in Applied Sciences, Engineering and Technology. Since leaving WPI, Zinsou has continued to work on SINDI within the Institute of Research for Development at UMMISCO, a research organization in Dakar, Senegal.

Mycetoma causes tumor-like lesions, often on the feet, where breaks in the skin and exposure to contaminated soil or water can provide a pathway for invading pathogens. Farmers, laborers, and people who walk barefoot are especially prone to mycetoma. If not treated, mycetoma can invade deep tissues, cause deformities, and impair the body’s ability to function.

Antibiotics or antifungal medications can be used to treat mycetoma, depending on the cause of the infection, but determining the cause is not always easy. Pathologists typically examine tissues and cells under a microscope to identify abnormal structures called “grains” that aid in diagnosis.