A research team at Worcester Polytechnic Institute (WPI) has received a three-year, $1.2 million grant from the National Science Foundation’s STEM+Computing Program to help high school teachers integrate biology and computer science tools and approaches in their classrooms. The project involves a diverse team that will develop curriculum to engage students and teachers in collecting their own biological data, and help design and use computational tools to analyze that data. Students will be motivated by working on a complex real-world problem, pollinator decline, and loss of biodiversity.

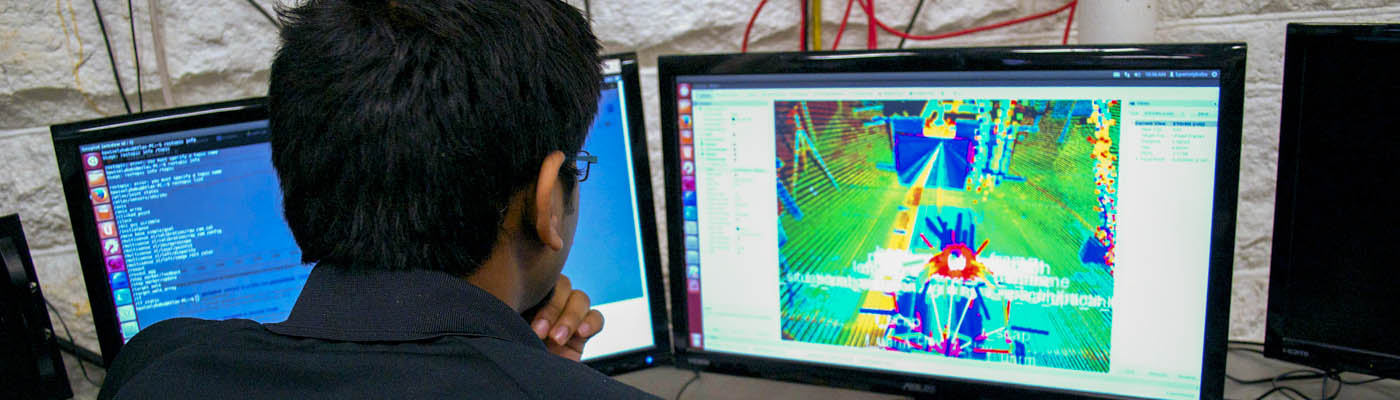

“It is critical in this information age for high school biology teachers to integrate computational thinking and approaches into their teaching,” said Elizabeth Ryder, associate professor of biology and biotechnology, and principal investigator of this research. “But this can be really difficult for a single teacher working in isolation. That’s why, in our work, we have assembled a transdisciplinary team, including university and high school faculty and students with expertise in biology, computer science, and education. We hope to show that teams like this are critically important in developing curriculum that really works to help teachers integrate science and computational thinking in the classroom.”

Ryder’s transdisciplinary team includes Robert Gegear, assistant professor of biology and biotechnology; Carolina Ruiz, associate professor of computer science; and Shari Weaver, assistant director of teacher preparation at WPI’s STEM Education Center, as well as WPI graduate and undergraduate students, and high school students. Ryder, Gegear, and Ruiz are also part of WPI’s Bioinformatics and Computational Biology Program. The team will work with four teachers from Nipmuc Regional High School in Upton, Mass., and Worcester Technical High School to develop modular software and teaching curriculum that can be used in classrooms ranging from introductory biology to advanced placement computer science. After piloting the curriculum in their own classrooms, these teachers will train other teachers in this approach at a summer institute at WPI, thus increasing the impact of the work.

“Computational thinking is becoming the language of science,” said Ruiz, who leads the computational aspects of the project. “We want to introduce students to this way of thinking early on. We hope the curriculum that our team will develop will eventually spread across the state, and nationwide.”

Ryder says because students become more motivated to learn when working on real-world problems, her team chose to focus the curriculum on pollinator and biodiversity decline. According to Gegear, who focuses on the ecological elements of the project, ecosystems are losing bumblebees and other pollinators at an alarming rate for unknown reasons.

“Through the curriculum that we develop, students will learn to develop and use computational tools to help ‘crowdsource’ the collection of ecological data, which will help us better understand why pollinators are in decline, what effect it is having on ecosystems, and how to stop it,” he said.

The effectiveness of the curriculum will be measured with surveys of curriculum quality and implementation feasibility, pre- and post-testing of both teachers and students on biology and computer science content knowledge and practices, and attitudes toward biology and computer science. One of the most important outcomes, Weaver said, is to boost student learning. “The goal is to have students deepen their understanding of science,” she said.

Eventually, Ryder’s team would like to see the transdisciplinary team approach to modular curriculum development they are piloting in this study utilized with other STEM disciplines.

“We envision other university–high school partnerships across the country utilizing our work as a blueprint to develop curriculum that integrates STEM and computer science approaches around real-world problems of all kinds,” Ryder says.