Under the moonlight

out on the hill

I hear the call

of a lone whip-poor-will

--From Poor Whip-Poor-Will by Jimmy Kennedy and Nat Simon

Once, the eponymous call of the whip-poor-will rang out across New England in the pre-dawn and twilight hours of spring and summer days. But today, the haunting, quickly whistled song of this mysterious nocturnal bird is heard by few, as the dry open woodlands and clearings it prefers for its breeding grounds have been largely lost to development or have become overgrown.

In Massachusetts, the whip-poor-will has been designated a “species of special concern,” which the state’s Endangered Species Act defines as a plant or animal that has “suffered a decline that could threaten the species if allowed to continue unchecked or that occurs in such small numbers or with such a restricted distribution or specialized habitat requirements that it could easily become threatened within the commonwealth.”

While the whip-poor-will will likely never again be a ubiquitous visitor to neighborhoods throughout the Northeast, the Massachusetts Department of Fisheries and Wildlife is working to maintain the population that calls the state home by protecting and managing the small number of sites that support at least one breeding pair, particularly the six locations that are home to 20 or more pairs. Efforts are also being made to create new whip-poor-will habitats by reintroducing “disturbance regime” in selected locations through controlled fires, logging, and other means.

With its cryptic coloration, large eyes, and stiff rictal bristles (or whiskers),which may play a role in locating or capturing flying insects,

the whip-poor-will is well equipped for life in the near darkness of spring and summer evenings.

Complicating efforts to protect and manage the state’s whip-poor-will population is a scarcity of detailed knowledge about the bird’s habits and lifecycle, including factors—like its reproductive success and habitat preferences—that directly affect its long-term prospects.

“There is a lot we don’t know about the whip-poor-will, and that’s why I wanted to get involved in this research,” says Marja Bakermans, associate teaching professor in Undergraduate Studies, who has embarked on a study aimed at casting light on one of the whip-poor-will’s most significant mysteries: its annual migration.

Solving the Migration Puzzle

A biologist with a PhD in natural resources from Ohio State University, Bakermans conducts research on wildlife, ecology, environmental science, and conservation biology, with a particular interest in promoting the conservation of biodiversity by maintaining viable wildlife populations across the landscape. Much of her research has focused on the ecology of migratory songbirds, particularly the cerulean warbler and the golden winged warbler, species found in North America that have experienced significant drops in populations due, in large part, to habitat loss.

As with the whip-poor-will, researchers, including Bakermans, have focused on the migratory habits of these warbler species to better understand the factors that are contributing to their decline, she says. “What we are looking at is migratory connectivity—connecting the non-breeding winter habitat to the breeding habitat. As we work to conserve species, we need to know where the threats are. And for our New England species, the threats may lie more on the wintering ground. We just don’t know.”

In fact, she says, very little is known about when and where whip-poor-wills migrate. “Most migratory birds have distinct breeding regions to which they return faithfully, but their wintering grounds can be less distinct. We don’t know if our New England birds go to Florida or Costa Rica, or how spread out they are. A recent paper by Canadian researchers did not find any whip-poor-wills wintering in Florida, but we are curious to see if some or ours might have been visiting Disney!”

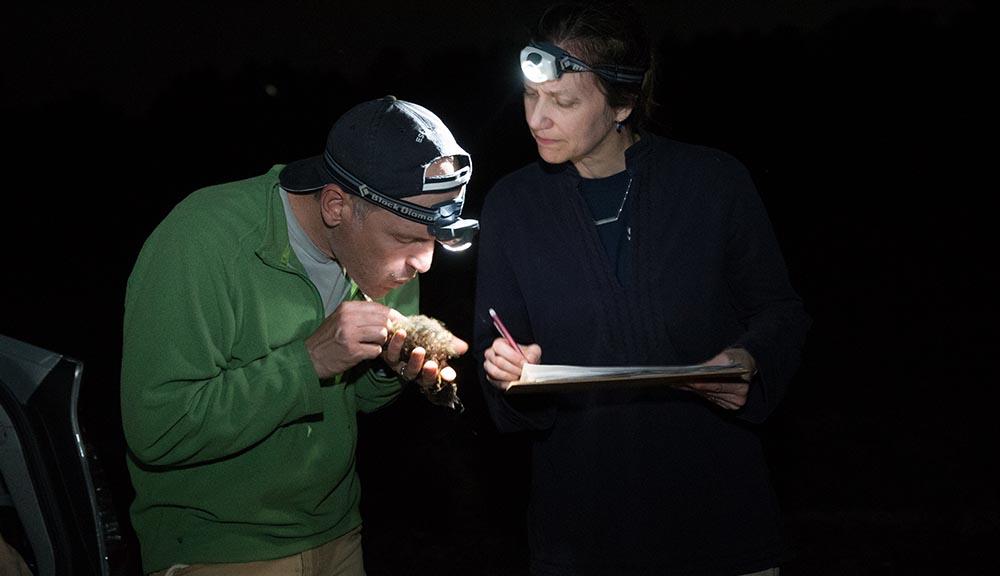

Bakermans uses a crochet hook to gently wrap the elastic bands of the location tracker around a whip-poor-will’s wings. The bird will wear the tracker like a tiny backpack.

Late Nights, Net Gains

In conjunction with the Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, where her husband, Andrew Vitz, is the state ornithologist, and with funding from the William P. Wharton Trust, a Massachusetts foundation that supports the study and conservation of nature, Bakermans and a team of WPI undergraduates have been conducting research in two areas in the state with large breeding populations: Joint Base Cape Cod, a military base at the western end of the Cape with a large tract of undeveloped land, and Bolton Flats Wildlife Management Area in Lancaster.

The team conducted field work in May and June of 2017, and have been back in the field this spring. The research entails a lot of late evenings. “One of the reasons there is so little natural history about these birds is because they are very cryptic,” Bakermans says, “which means they are only active at dawn and dusk, typically.” In addition, the birds are adorned in natural camouflage, making them even more difficult for average birders to spot.