A device that more than 80 percent of Americans virtually always have with them may become an early warning system for soldiers suffering from traumatic brain injuries (TBI) and infectious diseases, thanks to research by a team of computer scientists at Worcester Polytechnic Institute (WPI). The researchers are developing machine learning algorithms that will sort through a host of data collected by the sensors in smartphones to detect telltale signs of medical conditions that can affect a soldier’s readiness.

Computer science professors Emmanuel Agu, faculty director for WPI’s Healthcare Delivery Institute, and Elke Rundensteiner, director of the university’s Data Science Program, are developing this new technology with support from a four-year, $2.8 million award from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) through its Warfighter Analytics using Smartphones for Health (WASH) program.

The goal of WASH is to create a mobile application that passively assesses a soldier’s health—immediately and over time—with the goal of detecting potentially severe illnesses at their earliest stages, and pointing soldiers toward care. The system will not replace typical medical assessments, but will augment them by detecting problems outside of scheduled clinical appointments. In this way, the app could help flag small problems before they escalate and before they impair the readiness of soldiers or spread diseases like the flu, tuberculosis, and pneumonia through squadrons.

“Often times, soldiers may exhibit signs of brain injury or other illnesses, like infectious diseases, that could be sensed well before the full-blown symptoms impair their readiness,” said Agu, principal investigator for the project. “Our team will research and develop machine learning algorithms that tap into smartphone sensors to passively collect data about certain behaviors that we know are related to such health issues. This will enable continuous, real-time assessment of TBI and infectious diseases afflicting soldiers, who can then be contacted by a clinician to confirm their status.”

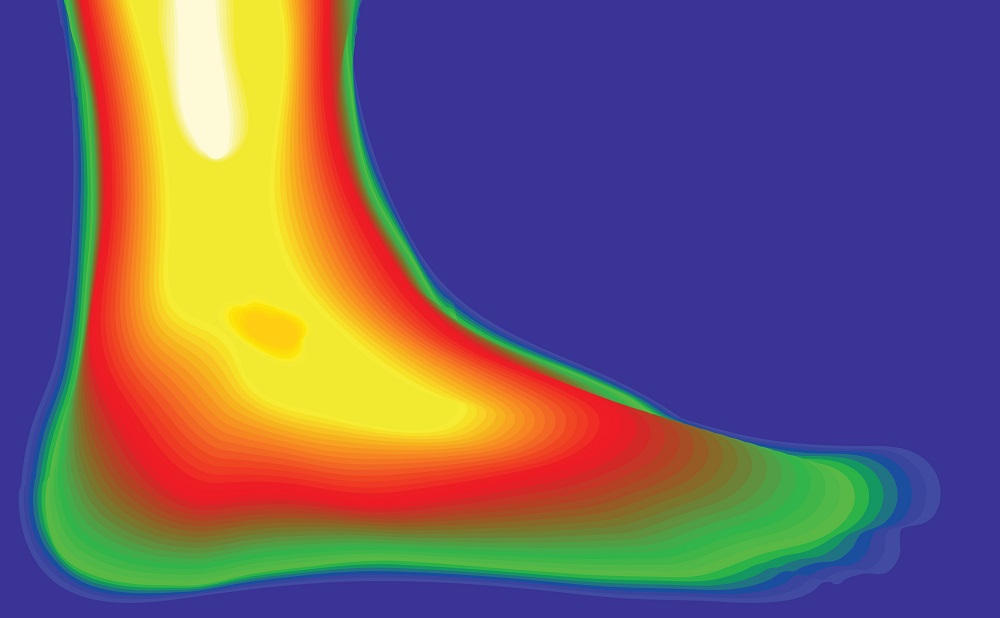

According to the Department of Defense (DOD), an estimated 22 percent of all combat casualties from Iraq and Afghanistan suffer brain injuries. The DOD and Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) are also monitoring cases of infectious diseases contracted during tours in Iraq or Afghanistan. Currently, a soldier’s condition is assessed using specialized medical tests and devices, such as a CT scan or MRI machine, that are available in doctor’s offices, clinics, and hospitals, though not always around the clock. With their computing power and array of sensors and processing technology, including cameras, microphones, accelerometers, facial recognition, fingerprint detection, and GPS, smartphones have the ability to continually capture what Agu calls “smartphone biomarkers,” which are data points and behavior that correspond to disease symptoms.

“Detecting changes in behavior patterns is critical for early identification of health concerns and unique health care needs, even before the illness fully manifests itself,” Agu said. “We can look for symptoms like slurred speech or reduced communication and social interaction that may indicate TBI, or coughing and fatigued movement typical of some infectious diseases, and we can trigger help earlier.”

Agu and Rundensteiner plan to test the utility of their approach, first through a study in which they will collect data from 100 volunteer subjects, and later, in a larger phase of the WASH project, through large-scale studies involving up to 100,000 subjects. These will include cohorts with TBI and infectious diseases being studied by other WASH teams. Guided by these results, the WPI team will build machine learning and deep learning algorithms that can instantly and continuously compare an individual patient’s biomarkers to biomarkers that are known to correlate well with symptoms of TBI and infectious diseases. Machine learning will enable the app to not only note symptoms, but to also calculate their severity.

“By processing data captured by numerous sensors on the smartphones of 100,000 patients, using open-source machine learning infrastructures and cloud computing power, we will gain the critical capability to infer the health status of individual smartphone users in near real-time and with great precision,” said Rundensteiner. “The technology we are creating through WASH, which will discover predictive patterns in massive data sets in real time, is bound to be transformative. In addition, the resulting smartphone sensor data set to be created through the DARPA WASH project will be one of the largest of its kind, representing a significant value and critical resource in its own right.”

Participation in the data gathering studies for the app will be voluntary and all data will be confidential and secure.

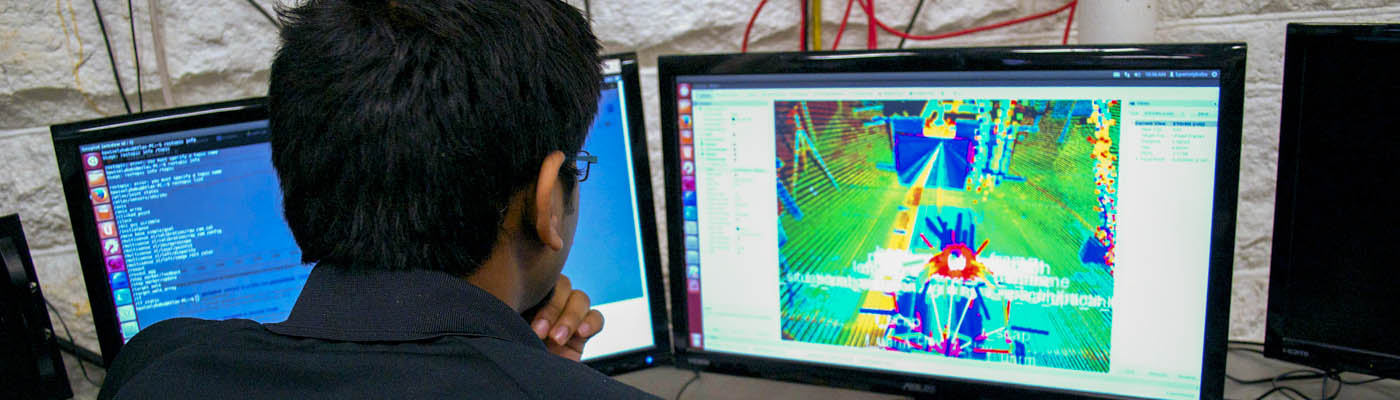

Five WPI PhD students are currently working on the DARPA-funded project, along with several undergraduate students. Additional personnel may join the project in the future.

DARPA dates back to the launch of Sputnik in 1957, with a mission to make pivotal investments in breakthrough technologies for national security.

“The military is frequently the first funder of big ideas, like the Internet, which decades later is benefiting and transforming society in a fundamental manner,” Agu said. “I think that someday the work we are doing to support soldiers through the WASH program may be used by society as a whole.”